All books 24glo.com/book/

Read online, download free ebook PDF, ePUB, MOBI docx txt AZW3

Davenport, Richard Alfred. Sketches of Imposture, Deception, and Credulity.

Originally published: 1837

CONTENTS

Effects of Incredulity and Credulity—Knowledge supposed to be Remembrance—Purpose of this Volume—Progress of rational Belief—Resemblance of Error to Truth—Contagious Nature of Excitement—Improved State of the Human Mind in Modern Times 13

Remote Origin of Oracles—Influence of Oracles—Opinions respecting them—Cause of the Cessation of Oracles—Superstition early systematized in Egypt—Bœotia early famous for Oracles—Origin of the Oracle of Dodona—Ambiguity of Oracular Responses—Stratagem of a Peasant—Oracles disbelieved by Ancient Philosophers—Cyrus and the Idol Bel—Source of Fire-Worshipping—Victory of Canopus over Fire—The Sphinx—Sounds heard from it—Supposed Cause of them—Mysterious Sounds at Nakous—Frauds of the Priests of Serapis—The Statue of Memnon—Oracle of Delphi—Its Origin—Changes which it underwent—The Pythoness—Danger attendant on her office—Tricks played by Heathen Priests—Origin of the Gordian Knot—The Knot is cut by Alexander—Ambrosian, Logan or Rocking Stones—Representations of them on Ancient Coins—Pliny’s Description of a Logan Stone in Asia—Stones at Sitney, in Cornwall, and at Castle Treryn—The latter is overthrown, and replaced—Logan Stones are Druidical Monuments 17

Susceptibility of the Imagination in the East—Mahomet—His Origin—He assumes the Title of the Apostle of God—Opposition to him—Revelations brought to Him by the Angel Gabriel—His Flight to Medina—Success of his Imposture—Attempt to poison him—His Death—Tradition respecting his Tomb—Account of his Intercourse with Heaven—Sabatai Sevi, a false Messiah—Superstitious Tradition among the Jews—Reports respecting the Coming of the Messiah—Sabatai pretends to be the Messiah—He is assisted by Nathan—Follies committed by the Jews—Honours paid to Sabatai—He embarks for Constantinople—His Arrest—He embraces Mahometanism to avoid Death—Rosenfeld, a German, proclaims himself the Messiah—His knavery—He is whipped and imprisoned—Richard Brothers announces himself as the revealed Prince and Prophet of the Jews—He dies in Bedlam—Thomas Muncer and his Associates—Their Fate—Matthias, John of Leyden, and other Anabaptist Leaders—They are defeated and executed—The French Prophets—Punishment of them—Miracles at the Grave of the Deacon Paris—Horrible Self-inflictions of the Convulsionaries—The Brothers of Brugglen—They are executed—Prophecy of a Lifeguardsman in London—Joanna Southcott—Her Origin, Progress, and Death—Folly of her Disciples—Miracles of Prince Hohenlohe 34

Account of Pope Joan—Artifice of Pope Sextus V.—Some Christian Ceremonies borrowed from the Jews and Pagans—Melting of the Blood of St. Januarius—Addison’s opinion of it—Description of the Performance of the Miracle—Miraculous Image of our Saviour at Rome—Ludicrous Metamorphosis of a Statue—Relics—Head of St. John the Baptist—Sword of Balaam—St. Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins—Self-Tormenting—Penances of St. Dominic the Cuirassier—The Crusades—Their Cause and Progress, and the immense numbers engaged in them. 62

Pretenders to Royalty numerous—Contest between the Houses of York and Lancaster gives rise to various Pretenders—Insurrection of Jack Cade—He is killed—Lambert Simnel is tutored to personate the Earl of Warwick—He is crowned at Dublin—He is taken Prisoner, pardoned, and made Scullion in the Royal Kitchen—Perkin Warbeck pretends to be the murdered Duke of York—He is countenanced by the King of France—He is acknowledged by the Duchess of Burgundy—Perkin lands in Scotland, and is aided by King James—He is married to Lady Catherine Gordon—He invades England, but fails—His Death—Pretenders in Portugal—Gabriel de Spinosa—He is hanged—The Son of a Tiler pretends to be Sebastian—He is sent to the Galleys—Gonçalo Alvarez succeeds him—He is executed—An Individual of talents assumes the Character of Sebastian—His extraordinary Behaviour in his Examinations—He is given up to the Spaniards—His Sufferings and dignified Deportment—His Fate not known—Pretenders in Russia—The first false Demetrius—He obtains the Throne, but is driven from it by Insurrection, and is slain—Other Impostors assume the same Name—Revolt of Pugatscheff—Pretenders in France—Hervegault and Bruneau assume the Character of the deceased Louis XVI. 73

Disguise of Achilles—Of Ulysses—Of Codrus—Fiction employed by Numa Pompilius—King Alfred disguised in the Swineherd’s Cottage—His Visit, as a Harper, to the Danish Camp—Richard Cœur de Lion takes the Garb of a Pilgrim—He is discovered and imprisoned—Disguises and Escape of Mary, Queen of Scots—Escape of Charles the Second, after the Battle of Worcester—Of Stanislaus from Dantzic—Of Prince Charles Edward from Scotland—Peter the Great takes the Dress of a Ship Carpenter—His Visit to England—Anecdote of his Conduct to a Dutch Skipper—Stratagem of the Princess Ulrica of Prussia—Pleasant Deception practised by Catherine the Second of Russia—Joan of Arc—Her early Life—Discovers the King when first introduced at Court—She compels the English to raise the Siege of Orleans—Joan leads the King to be crowned at Rheims—She is taken Prisoner—Base and barbarous Conduct of her Enemies—She is burned at Rouen—The Devil of Woodstock—Annoying Pranks played by it—Explanation of the Mystery—Fair Rosamond 86

Characteristic Mark of a skilful General—Importance anciently attached to military Stratagems—The Stratagem of Joshua at Ai, the first which is recorded—Stratagem of Julius Cæsar in Gaul—Favourable Omen derived from Sneezing—Artifice of Bias at Priene—Telegraphic Communication—Mode adopted by Hystiæus to convey Intelligence—Relief of Casilinum by Gracchus—Stratagem of the Chevalier de Luxembourg to convey Ammunition into Lisle—Importance of concealing the Death of a General—The manner in which the Death of Sultan Solyman was kept secret—Stratagem of John Visconti—Stratagem of Lord Norwich at Angoulème—Capture of Amiens by the Spaniards—Manner in which the Natives of Sonia threw off the Yoke 109

Former Prevalence of Malingering in the Army; and the Motives for it—Decline of the Practice—Where most Prevalent—The means of Simulation reduced to a System—Cases of simulated Ophthalmia in the 50th Regiment—The Deception wonderfully kept up by many Malingerers—Means of Detection—Simulated Paralysis—Impudent Triumph manifested by Malingerers—Curious case of Hollidge—Gutta Serena, and Nyctalopia counterfeited—Blind Soldiers employed in Egypt—Cure, by actual cautery, of a Malingerer—Simulation of Consumption and other Diseases—Feigned Deafness—Detection of a Man who simulated Deafness—Instances of Self-mutilation committed by Soldiers—Simulation of Death 118

The Bottle Conjuror—Advertisements on this Occasion—Riot produced by the Fraud—Squibs and Epigrams to which it gave rise—Case of Elizabeth Canning—Violent Controversy which arose out of it—She is found guilty of Perjury and transported—The Cock Lane Ghost—Public Excitement occasioned by it—Detection of the Fraud—Motive for the Imposture—The Stockwell Ghost—The Sampford Ghost—Mystery in which the Affair was involved—Astonishing Instance of Credulity in Perigo and his Wife—Diabolical Conduct of Mary Bateman—She is hanged for Murder—Metamorphosis of the Chevalier d’Eon—Multifarious Disguises of Price, the Forger—Miss Robertson—The fortunate Youth—The Princess—Olive—Caraboo—Pretended Fasting—Margaret Senfrit—Catherine Binder—The Girl of Unna—The Osnaburg Girl—Anne Moore 126

Controversy respecting the Works of Homer; Arguments of the Disputants—Controversy on the supposed Epistles of Phalaris—Opinion of Sir William Temple on the Superiority of the Ancients—Dissertation of Dr. Bentley on the Epistles of Phalaris—He proves them to be a Forgery—Doubts as to the Anabasis being the Work of Xenophon—Arguments of Mr. Mitford in the Affirmative—Alcyonius accused of having plagiarised from, and destroyed, Cicero’s Treatise “De Gloria”—Curious Mistake as to Sir T. More’s Utopia—The Icon Basilike—Disputes to which it gave rise—Arguments, pro and con, as to the real Author of it—Lauder’s Attempt to prove Milton a Plagiarist—Refutation of him by Dr. Douglas—His interpolations—George Psalmanazar—His Account of Formosa—His Repentance and Piety—Publication of Ossian’s Poems by Mr. Macpherson—Their Authenticity is doubted—Report of the Highland Society on the Subject—Pseudonymous and anonymous Works—Letters of Junius—The Drapier’s Letters—Tale of a Tub—Gulliver’s Travels—The Waverley Novels—Chatterton and the Rowley Poems—W. H. Ireland and the Shakspearian Forgeries—Damberger’s pretended Travels—Poems of Clotilda de Surville—Walladmor—Hunter, the American—Donville’s Travels in Africa 147

Fashion of decrying modern Artists—M. Picart asserts the Merit of modern Engravers—Means employed by him to prove the Truth of his Assertions—“The innocent Impostors”—Goltzius imitates perfectly the Engravings of Albert Durer—Marc Antonio Raimondi is equally successful—Excellent Imitation of Rembrandt’s Portrait of Burgomaster Six—Modern Tricks played with respect to Engraved Portraits—Sir Joshua Reynolds metamorphosed into “The Monster.” 191

Ancient Memorials of Geographical Discoveries—Mistakes arising from them—Frauds to which they gave occasion—Imposture of Evemerus—Annius of Viterbo wrongfully charged with forging Inscriptions—Spurious works given to the World by him—Forged Inscriptions put on statues by ignorant modern Sculptors—Spurious Medals—Instances of them in the Cabinet of Dr. Hunter—Coins adulterated by Grecian Cities—Evelyn’s Directions for ascertaining the Genuineness of Medals—Spurious Gold Medals—Tricks of the Manufacturers of Pseudo-Antique Medals—Collectors addicted to pilfering Rarities—Medals swallowed by Vaillant—Mistakes arising from Ignorance of the Chinese Characters. 195

First Opening of the Regalia to public Inspection—Edwards appointed Keeper—Plan formed by Blood to steal the Regalia—He visits the Tower with his pretended Wife—Means by which he contrived to become intimate with Edwards—His Arrangements for carrying his Scheme into Execution—He knocks down Edwards, and obtains Possession of the Jewels—Fortunate Chance by which his Scheme was frustrated—He is taken—Charles II. is present at his Examination—Blood contrives to obtain a Pardon, and the Gift of an Estate from the King. 201

Horrible nature of the Superstition of Vampyrism—Persons attacked by Vampyres become Vampyres themselves—Signs by which a Vampyre was known—Origin of one of the signs—Effect attributed to Excommunication in the Greek church—Story of an excommunicated Greek—Calmet’s theory of the origin of the Superstition respecting Vampyres—St. Stanislas—Philinnium—The Strygis supposed to have given the idea of the Vampyre—Capitulary of Charlemagne—Remedy against attacks from the Demon—Anecdote of an impudent Vampyre—Story of a Vampyre at Mycone—Prevalence of Vampyrism in the north of Europe—Walachian mode of detecting Vampyres. 205

Feats of Jugglers formerly attributed to witchcraft—Anglo-Saxon Gleemen—Norman Jugglers or Tregatours—Chaucer’s Description of the Wonders performed by them—Means probably employed by them—Recipe for making the Appearance of a Flood—Jugglers fashionable in the Reign of Charles II.—Evelyn’s Account of a Fire-eater—Katterfelto—Superiority of Asiatic and Eygptian pretenders to magical Skill—Mandeville’s Account of Juggling at the Court of the Great Khan—Extraordinary Feats witnessed by the Emperor Jehanguire—Ibn Batuta’s Account of Hindustanee Jugglers—Account of a Bramin who sat upon the Air—Egyptian Jugglers—Mr. Lane’s Account of the Performance of one of them—Another fails in satisfying Captain Scott. 212

Hold taken on the public Mind by Prodigies—Dutch Boy with Hebrew Words on the Iris of each Eye—Boy with the word Napoleon in the Eye—Child with a Golden Tooth—Speculations on the Subject—Superstition respecting changeling Children in the Isle of Man—Waldron’s Description of a Changeling—Cases of extraordinary Sleepers—The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus—Men supposed, in the northern Regions, to be frozen during the Winter, and afterwards thawed into Life again—Dr. Oliver’s Case of a Sleeper near Bath—Dr. Cheyne’s Account of Colonel Townshend’s power of voluntarily suspending Animation—Man buried alive for a Month at Jaisulmer—The Manner of his Burial, and his Preparation for it. 221

Origin of Alchemy—Argument for Transmutation—Golden Age of Alchemy—Alchemists in the 13th century—Medals metaphorically described—Jargon of Dr. Dee—The Green Lion—Roger Bacon—Invention of Gunpowder—Imprisonment of Alchemists—Edict of Henry VI.—Pope John XXII.—Pope Sixtus V.—Alchemy applied to Medicine—Paracelsus—Evelyn’s hesitation about Alchemy—Narrative of Helvetius—Philadept on Alchemy—Rosicrucians—A Vision—Hayden’s description of Rosicrucians—Dr. Price—Mr. Woulfe—Mr. Kellerman. 230

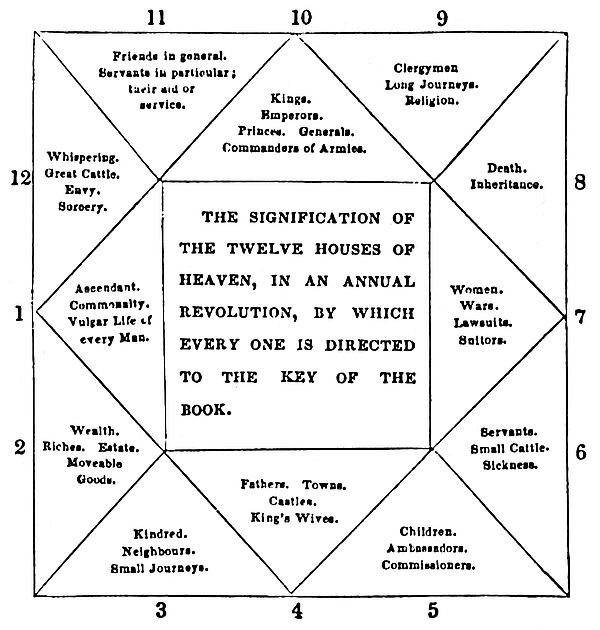

Supposed Origin of Astrology—Butler on the Transmission of Astrological Knowledge—Remarks on Astrology by Hervey—Petrarch’s Opinion of Astrology—Catherine of Medicis—Casting of Nativities in England—Moore’s Almanack—Writers for and against Astrology—Horoscope of Prince Frederick of Denmark—Astrologers contributed sometimes to realize their own Predictions—Caracalla 244

State of Medicine in remote Ages—Animals Teachers of Medicine—Gymnastic Medicine—Cato’s Cure for a Fracture—Dearness of ancient Medicines and Medical Books—Absurdity of the ancient Materia Medica: Gold, Bezoar, Mummy—Prescription for a Quartan—Amulets—Virtues of Gems—Corals—Charms—Charm for sore Eyes—Medicine connected with Astrology—Cure by Sympathy—Sir Kenelm Digby—The real Cause of the Cure—The Vulnerary Powder, &c.—The Royal Touch—Evelyn’s Description of the Ceremony—Valentine Greatrakes—Morley’s Cure for Scrofula—Inoculation—Vaccination—Dr. Jenner—Animal Magnetism—M. Loewe’s Account of it—Mesmer, and his Feats—Manner of Magnetizing—Report of a Commission on the Subject—Metallic Tractors—Baron Silfverkielm and the Souls in White Robes—Mr. Loutherbourg—Empirics—Uroscopy—Mayersbach—Le Febre—Remedies for the Stone—The Anodyne Necklace—The Universal Medicine 250

Superstition of the Hindoos—The Malays—Asiatic Superstitions—The Chinese—Miracle of the Blessed Virgin—Stratagem of an Architect—Michael Angelo’s Cupid—Statue of Charles I.—Ever-burning Sepulchral Lamps—Lamp in the Tomb of Pallas—The art of Mimicry—Superiority of the Ancients—Fable of Proteus—Personation of the insane Ajax—Archimimes at funerals—Demetrius the cynic converted—Acting portraits and historical pictures—War dances of the American Indians—The South Sea Bubble—Gay the poet—Law’s Mississippi Scheme—Numerous Bubbles—Speculations in 1825 274

OF

IMPOSTURE, DECEPTION,

AND

CREDULITY.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS.

Incredulity has been said, by Aristotle, to be the foundation of all wisdom. The truth of this assertion might safely be disputed; but, on the other hand, to say that credulity is the foundation of all folly, is an assertion more consonant to experience, and may be more readily admitted; and the contemplation of this subject forms a curious chapter in the history of the human mind.

A certain extent of credulity, or, more properly, belief, may, indeed, be considered as absolutely necessary to the well-being of social communities; for universal scepticism would be universal distrust. Nor could knowledge ever have arrived at its present amazing height, had every intermediate step in the ladder of science, from profound ignorance and slavery of intellect, been disputed with bigoted incredulity.

It has been said, that all knowledge is remembrance, and all ignorance forgetfulness,—alluding to the universal knowledge which, in the opinion of the schoolmen, our first father, Adam, possessed before the fall,—and that the subsequent invention of arts and sciences was only a partial recovery or recollection, as it were, of what had been originally well known. The undefined aspirations of many minds, to seek for what is distant and least understood, in preference to that near at hand and more in unison with our general state of knowledge, seem to favour this idea.

It will be the endeavour of the following pages to show that the credulity of the many—in some cases synonymous with the foolish—has been, from the beginning, most readily imposed upon by the clever and designing few. It is a curious task to investigate the gradual developement of rational belief, as exhibited in the proportionate disbelief and exposure of those things which, in earlier ages, were considered points of faith, and to doubt which was a dangerous heresy; and how, at first, the arts and sciences were weighed down and the advantages to be derived from them neutralized, by the fallacies of misconception or fanaticism. We are, in spite of ourselves, the creatures of imagination, and the victims of prejudice, which has been justly called the wrong bias of the soul, that effectually keeps it from coming near the path of truth; a task the more difficult to accomplish, since error often bears so near a resemblance to it. Error, indeed, always borrows something of truth, to make her more acceptable to the world, seldom appearing in her native deformity; and the subtilty of grand deceivers has always been shown in grafting their greatest errors on some material truths, and with such dexterity, that Ithuriel’s spear alone, whose touch

would have power to reveal them.

Many, and even contradictory, causes might be assigned for the constant disposition towards credulity; the mind is prone to believe that for which it most anxiously wishes; difficulties vanish in desire, which thus becomes frequently the main cause of success. Thus, when Prince Henry, believing his father dead, had taken the crown from his pillow, the King in reproach said to him,[1]

Belief is often granted on trust to such things as are above common comprehension, by some, who would thus flatter themselves with a superiority of judgment; on the other hand, what all around put faith in, the remaining few will, from that circumstance, easily believe. This is seen in times of popular excitement, when an assertion, quite at variance with common sense or experience, will run like a wild-fire through a city, and be productive of most serious results. It would appear that this springs from that inherent power of imitation, which is singularly exemplified even in particular kinds of disease,—comitial, as they were called by the Romans, from their frequent occurrence in assemblies of the people,—and, more fatally, when it impels us to “follow a multitude to do evil.”

After a long and dreary period of ignorance, the nations of Europe began to arouse themselves from the lethargy in which they had been plunged; religious enthusiasm then awakened the ardour of heroism, and the wild but fascinating spirit of chivalry—whose actions were the offspring of disinterested valour, that looked for no reward but the smile of favouring beauty or grateful tear of redressed misfortune,—taught the world that humanity and benevolence were no less meritorious than undaunted courage and athletic strength.

Knowledge, however, advanced with slow and timid steps from the cells of the monks, in which she had been obliged to conceal herself, whilst her rival, Ignorance, had been exalted to palaces and thrones. From the period which succeeded that twilight of the Goths and Vandals, when all the useful arts were obscured and concealed by indolent indifference, we shall find that each succeeding age happily contributed to enlighten the world by the revival and gradual improvement of the arts and sciences; a corresponding elevation in the general sagacity of the human mind was the natural consequence: this can readily be shown by the proportionate decrease of the numerous methods by which specious impostors lived upon the credulity of others.

Few, it is to be hoped, in the present day seek consolation for disappointment in the mysteries of astrological judgments, or attribute their ill-success in life to an evil conjunction of the stars, as revealed by the deluding horoscope of a caster of nativities.

That age has at length passed away, when the search after the philosopher’s stone, or the universal solvent, terminated a life of incredible toil and hopeless expectation, in poverty and contempt. But there are still many who neglect the experience of the past, and, anxious to know their future fate, seek it in the fortune-teller’s cards; or, unhappily, a prey to some of those ills that flesh is heir to, would rather seek to expedite their cure by some specious but empirical experiment, than wait for the slower but surer results of time and experience.

CHAPTER II.

ON ANCIENT ORACLES, ETC.

The knowledge of the origin of the ancient oracles is lost in the distance of time; yet it seems reasonable to suppose, that traditionary accounts and confused recollections of the revelations graciously vouchsafed to Noah, to Abraham, and the Patriarchs, more especially Moses, may have been the foundation of these oracles, which were venerated in ancient times; and established in temples, which were, in some instances, supposed to be even the abode of the gods themselves: thus, Apollo was supposed to take up his occasional residence at Delphos, Diana at Ephesus, and Minerva at Athens.

The manner of prophecy was various, but that employed by oracles enjoyed the greatest repute; because they were believed to proceed, in a most especial manner, from the gods themselves. Every thing of essential consequence being, therefore, referred to them by the heads of states, oracles obtained a powerful influence over the minds of the people; and this popular credulity offered tempting opportunities to the priests for carrying on very lucrative impostures, nor did they disdain or neglect to take advantage of those opportunities. Added to this, the different functions of the gods, and the different and often opposite parts which they were made to take in human affairs by the priests and poets, were plentiful sources of superstitious rites, and therefore of emolument to those who, in consequence either of office or pretension, were supposed to have immediate communications with the deity in whose temples they presided.

Much has been written on this subject; and some have even gone so far as to suppose that Divine permission was granted to certain demons, or evil spirits, to inhabit pagan shrines, and thence, by ambiguous answers, to deceive, and often to punish, those who sought by their influence to read the forbidden volume of futurity.

This doctrine was strenuously opposed by Van Dale; and Mœbius (of Leipsic), although opposed to Van Dale’s opinion, allows that oracles did not cease to grant responses immediately at the coming of Christ; and this has been considered a sufficient proof as well as argument, that demons did not deliver oracular responses; but that those responses were impostures and contrivances of the priests themselves.

The true cause of the cessation of oracular prophecy, however, appears to be, that the minds of men became enlightened by the wide-spreading of the Christian faith; and by the circumstance, that their superstition was compromised by the metamorphoses of their favourite heroes and deities into saints and martyrs. As an instance of which, it will hereafter be shown, that the statues of the ancient gods, even to this day, are allowed to stand and hold places in the churches and cathedrals of many Catholic countries.

Those who argue that oracles ceased immediately at the coming of Christ, relate, in confirmation of their opinion, that Augustus having grown old, became desirous of choosing a successor, and went, in consequence, to consult the oracle at Delphos. No answer was given, at first, to his inquiry, though he had spared no expense to conciliate the oracle. At last, however, the priestess is reported to have said, “the Hebrew Infant, to whom all gods render obedience, chases me hence; He sends me to the lower regions; therefore depart this temple, without speaking more.”

Superstition was formed into a system in Egypt at an age prior to our first accounts of that country. Vast temples were built, and innumerable ceremonies established; the same body, forming the hereditary priesthood and the nobility of the nation, directed with a high hand the belief and consciences of the people; and prophecy was not only among their pretensions, but perhaps the most indispensable part of their office.

Bœotia was also a country famous for the number of its oracles, and from its localities was well suited for such impostures, being mountainous and full of caverns, by means of which sounds and echoes, apparently mysterious, could be easily multiplied to excite the astonishment and terror of the supplicants.

Herodotus informs us, that one of the first oracles in Greece was imported from the Egyptian Thebes. It happened, says Mr. Mitford in his History of Greece, that the master of a Phœnician vessel carried off a woman, an attendant of the temple of Jupiter, at Thebes on the Nile, and sold her in Thesprotia, a mountainous tract in the northwestern part of Epirus, bordering on the Illyrian hordes. Reduced thus unhappily to slavery among barbarians, the woman, however, soon became sensible of the superiority which her education in a more civilized country gave her over them; and she conceived hopes of mending her condition, by practising upon their ignorance what she had acquired of those arts which able hands imposed upon a more enlightened people. She gave out that she possessed all the powers of prophecy to which the Egyptian priests pretended; that she could discover present secrets, and foretell future events.

Her pretensions excited curiosity, and brought numbers to consult her. She chose her station under the shade of a spreading oak, where, in the name of the god Jupiter, she delivered answers to her ignorant inquirers; and shortly her reputation as a prophetess extended as far as the people of the country themselves communicated.

These simple circumstances of her story were afterwards, according to the genius of those ages, turned into a fable, which was commonly told, in the time of Herodotus, by the Dodonæan priests. A black pigeon, they said, flew from Thebes in Egypt to Dodona, and, perching upon an oak, proclaimed with human voice, “That an oracle of Jupiter should be established there.” Concluding that a divinity spoke through the agency of the pigeon, the Dodonæans obeyed the mandate, and the oracle was established. The historian accounts for the fiction thus: the woman on her arrival speaking in a foreign dialect, the Dodonæans said she spoke like a pigeon; but afterwards, when she had acquired the Grecian speech and accent, they said the pigeon spoke with a human voice.

The trade of prophecy being both easy and lucrative, the office of the prophetess was readily supplied both with associates and successors. A temple for the deity and habitations for his ministers were built; and thus, according to the evidently honest, and apparently well-founded and judicious, account of Herodotus, arose the oracle of Jupiter at Dodona, the very place where tradition, still remaining to the days of that writer, testified that sacrifices had formerly been performed only to the nameless god.

The responses of the oracles, though given with some appearance of probability, were for the most part ambiguous and doubtful; but it must be acknowledged that the priests were very clever persons, since, while they satisfied for the time the wishes of others, they were so well able to conceal their own knavery. A fellow, it is said, willing to try the truth of Apollo’s oracle, asked what it was he held in his hand—holding at the time a sparrow under his cloak—and whether it was dead or alive—intending to kill or preserve it, contrary to what the oracle should answer—but it replied, that it was his own choice whether that which he held should live or die.

Many of the sages and other great men evidently paid no regard, or real veneration, to the oracles, beyond what policy dictated to preserve their influence over others.

The researches of modern antiquaries and travellers have discovered the machinery of many artifices of the priests of the now deserted fanes, which sufficiently account for the apparent miracles exhibited to the eye of ignorance. There remain many instances of this kind to show how general this system of imposture has been in all ages; and, as may be supposed, the priests did not fail to exact a liberal payment in advance.

Cyrus,—according to the apocryphal tradition,—a devout worshipper of the idol Bel, was convinced by the prophet Daniel of the imposture of this supposed mighty and living god, who was thought to consume every day twelve measures of fine flour, forty sheep, and six vessels of wine, which were placed as an offering on the altar. These gifts being presented as usual, Daniel commanded ashes to be strewed on the floor of the temple, round the altar on which the offerings were placed; and the door of the temple to be sealed in the presence of the king. Cyrus returned on the following day, and seeing the altar cleared of what was placed thereon, cried out “Great art thou, O Bel, and in thee is no deceit!” but Daniel, pointing to the floor, the king continues, “I see the footsteps of women and children!” The private door at the back of the altar leading to the dwellings of the priests was then discovered; their imposture clearly proved, they were all slain, and the temple was destroyed.

The circumstance of fire being so frequently an object of veneration amongst pagans, is thought to have arisen thus: the sun, as a source of light and heat, was the most evident and most benignant of the natural agents; and was worshipped, accordingly, as a first cause, rather than as an effect; as however it was occasionally absent, it was typified by fire, which had the greatest analogy to it.

This element, first respected only as the representative of the sun, in time became itself the object of adoration among the Chaldeans; and Eusebius relates the following circumstance with respect to it. The Chaldeans asserted that their god was the strongest and most powerful of all gods; since they had not met with any one that could resist his force; so that whenever they happened to seize upon any deities, which were worshipped by other nations, they immediately threw them into the fire, which never failed of consuming them to ashes, and thus the god of the Chaldeans came to be publicly looked upon as the conqueror of all other gods: at length a priest of Canopus, one of the Egyptian gods, found out the means to destroy the great reputation which fire had acquired. He caused to be formed an idol of a very porous earth, with which pots were commonly made to purify the waters of the Nile; the belly of this statue, which was very capacious, was filled with water, the priest having first made a great many little holes and stopped them with wax. He then challenged the fire of the Chaldeans to dispute with his god Canopus. The Chaldeans immediately prepared one, and the Egyptian priest set his statue on it; no sooner did the fire reach the wax than it dissolved, the holes were opened, the water passed through, and the fire was extinguished. Upon this a report was soon spread, that the god Canopus had conquered and destroyed the god of the Chaldeans. As a memorial of their victory, the Egyptians always afterwards made their idols with very large bellies.

The celebrated sphinx, still more interesting as a wonderful production of art, is said to have been made by an Egyptian king, in memory of Rhodope of Corinth, with whom he was passionately in love: yet it was subsequently considered as an oracle, which, if consulted at the rising of the sun, gave prophetic answers. There has lately been discovered a large hole in the head; in which the priests are supposed to have concealed themselves, for the purpose of deluding the people. At sunrise music was said to be heard. The latter might even occur from natural causes. Messieurs Jomard, Jollois, and Devilliers heard at sunrise, in a monument of granite, placed in the centre of that spot on which the palace of Karnak stood, a noise resembling that of a string breaking; this was found on attentive examination to proceed from a natural phenomenon, occurring near the situation of the sphinx. Of this circumstance the ingenuity of the priests would no doubt be sure to avail themselves; and this may also account for the hour of sunrise being chosen for the oracular responses.

To confirm the probability of this solution of the mystery, it may be mentioned that Baron Humboldt was informed by most credible witnesses, that subterranean sounds, like those of an organ, are heard towards sunrise by those who sleep upon the granite rocks on the banks of the Oroonoko. Those sounds he philosophically supposes may arise from the difference of temperature between the external air and that contained in the narrow and deep crevices of the rocks; the air issuing from which may be modified by its impulse against the elastic films of mica projecting into the crevices; producing, in fact, a natural and gigantic eolina, the simple but beautiful arrangement of musical chords which is now so commonly heard.

A somewhat similar phenomenon, which gives rise to an Arab superstition, occurs about three leagues from Tor, on the Red Sea. The spot, which is half a mile from the sea, bears the name of Nakous, or the Bell. It is about three hundred feet high, and eighty feet wide, presents a steep declivity to the sea, and is covered by sand, and surrounded by low rocks, in the form of an amphitheatre. The sounds which it emits are not periodical, but are heard at all hours and at all seasons. The place was twice visited by Mr. Gray. On the first visit, after waiting a quarter of an hour, he heard a low continuous murmuring sound beneath his feet, which, as it increased in loudness, gradually changed into pulsations, resembling the ticking of a clock. In five minutes more it became so powerful as to resemble the striking of a clock, and, by its vibrations, to detach the sand from the surface. When he returned, on the following day, he heard the sound still louder than before. Both times the air was calm, and the sky serene; so that the external air could have had no share in producing the phenomenon; nor could he find any crevice by which it could penetrate. The noise is affirmed by the people of Tor to frighten and render furious the camels that hear it; and the Arabs of the desert poetically ascribe it to the bell of a convent of monks, which convent they believe to have been miraculously preserved under ground. Seetzen, another visiter, attributes the phenomenon to the rolling down of the sand.

Rufinus informs us that, when it was destroyed by order of Theodosius, the temple of Serapis at Alexandria was found to be full of secret passages and machines, contrived to aid the impostures of the priests; among other things, on the eastern side of the temple, was a little window, through which, on a certain day of the year, the sunbeams entering fell on the mouth of the statue of Memnon. At the same moment an iron image of the sun was brought in, which, being attracted by a large loadstone fixed in the ceiling, ascended up to the image. The priests then cried out, that the sun saluted their god.

This Memnon was said to be the son of Tithonus and Aurora, and a statue of him in black marble was set up at Thebes. It is also related that the mouth of the statue, when first touched by the rays of the rising sun, sent forth a sweet and harmonious sound, as though it rejoiced when its mother Aurora appeared; but, at the setting of the sun, it sent forth a low melancholy tone, as if lamenting its mother’s departure.

On the left leg of one of the colossal figures called Memnon are engraved the names of many celebrated personages, who have borne witness, at different times, of their having heard the musical tones which proceeded from the statue on the rising and setting of the sun. Strabo was an ear-witness to the fact that an articulate sound was heard, but doubted whether it came from the statue.

The oracle which held the greatest reputation, and extended it over the world, was Delphi; yet upon what slight grounds were the minds of people led captive by the love of the marvellous and a proneness to superstition! Of this celebrated place so many fables are related, some of them referring to times long before any authentic account of the existence of such an oracle, that it is difficult to decide upon the real period.

On the southern side of Mount Parnassus, within the western border of Phocis, against Locris, and at no great distance from the seaport towns of Crissa and Cirrha, the mountain-crags form a natural amphitheatre, difficult of access, in the midst of which a deep cavern discharged from a narrow orifice a vapour powerfully affecting the brain of those who came within its influence. This was first brought into public notice by a goatherd, whose goats, browsing on the brink, were thrown into singular convulsions; upon which the man, going to the spot, and endeavouring to look into the chasm, became himself agitated like one frantic. These extraordinary circumstances were communicated through the neighbourhood; and the superstitious ignorance of the age immediately attributed them to a deity residing in the place. Frenzy of every kind among the Greeks, even in more enlightened times, was supposed to be the effect of divine inspiration; and the incoherent speeches of the frantic were regarded as prophetical. This spot, formerly visited only by goats, now became an object of extensive curiosity. It was said to be the oracle of the goddess Earth. The rude inhabitants from all the neighbouring parts resorted to it, for information concerning futurity; to obtain which any one of them inhaled the vapour, and whatever he uttered in the ensuing intoxication passed for prophecy. This was found dangerous, however, as many, becoming giddy, fell into the cavern and were lost; and in an assembly it was agreed that one person should alone receive the inspiration, and render the responses of the divinity. A virgin was preferred for the sacred office, and a frame prepared, resting on three feet, whence it was called tripod. The place bore the name of Pytho, and thence the title of Pythoness, or Pythia, became attached to the prophetess. By degrees, a rude temple was built over the cavern, priests were appointed, ceremonies were prescribed, and sacrifices were performed. A revenue was necessary. All who would consult the oracle henceforward must come with offerings in their hands. The profits produced by the prophecies of the goddess Earth beginning to fail, the priests asserted that the god Neptune was associated with her in the oracle. The goddess Themis was then reported to have succeeded mother Earth. Still new incentives to public credulity and curiosity became necessary. Apollo was a deity of great reputation in the islands, and in Asia Minor, but had at that time little fame on the continent of Greece. At this period, a vessel from Crete came to Crissa, and the crew landing proceeded up Mount Parnassus to Delphi. It was reported that the vessel and crew, by a preternatural power, were impelled to the port, accompanied by a dolphin of uncommon magnitude, who discovered himself to be Apollo, and who ordered the crew to follow him to Delphi and become his ministers. Thus the oracle recovered and increased its reputation. Delphi had the advantage of being near the centre of Greece, and was reported to be the centre of the earth; miracles were invented to prove so important a circumstance, and the navel of the earth was among the titles which it acquired. Afterwards vanity came in aid of superstition, in bringing riches to the temple: the names of those who made considerable presents were always registered, and exhibited in honour of the donors.

The Pythoness was chosen from among mountain cottagers, the most unacquainted with mankind that could be found. It was required that she should be a virgin, and originally taken when very young; and once appointed, she was never to quit the temple. But, unfortunately, it happened that one Pythoness made her escape; her singular beauty enamoured a young Thessalian, who succeeded in the hazardous attempt to carry her off. It was afterwards decreed that no Pythoness should be appointed under fifty years of age.

This office appears not to have been very desirable. Either the emanation from the cavern, or some art of the managers, threw her into real convulsions. Priests, entitled prophets, led her to the sacred tripod, force being often necessary for the purpose, and held her on it, till her frenzy rose to whatever pitch was in their judgment most fit for the occasion. Some of the Pythonesses are said to have expired almost immediately after quitting the tripod, and even on it. The broken accents which the wretch uttered in her agony were collected and arranged by the prophets, and then promulgated as the answer of the god. Till a late period, they were always in verse. The priests had it always in their power to deny answers, delay them, or render them dubious or unintelligible, as they judged most advantageous for the credit of the oracle. But if princes or great men applied in a proper manner for the sanction of the god to any undertaking, they seldom failed to receive it in direct terms, provided the reputation of the oracle for truth was not liable to immediate danger from the event.

Theophrastus, bishop of Alexandria, showed the inhabitants of that town the hollow statue into which the former priests of the pagan oracle had privately crept whilst delivering their responses; and a modern traveller corroborates this fact, by a similar discovery made among the excavations at Pompeii. “In the temple of Isis,” says Dr. J. Johnson, “we see the identical spot where the priests concealed themselves, whilst delivering the oracles that were supposed to proceed from the mouth of the goddess. There were found the bones of the victims sacrificed; and in the refectory of the abstemious priests were discovered the remains of ham, fowls, eggs, fish, and bottles of wine. These jolly friars were carousing most merrily, and no doubt laughing heartily at the credulity of mankind, when Vesuvius poured out a libation on their heads which put an end to their mirth.”[2]

“To cut the Gordian knot” has long been proverbial for an independent and unexpected way of overcoming difficulties, however great. It took its rise from a circumstance related with some variations by several ancient authors, and with great simplicity by Arrian; it is the more a curiosity as coming from a man of his eminence in his enlightened age.

At a remote period, says he, a Phrygian yeoman, named Gordius, was holding his own plough on his own land, when an eagle perched on the yoke and remained whilst he continued his work. Wondering at a matter so apparently preternatural, he deemed it expedient to consult some person among those who had reputation for expounding indications of the divine will. In the neighbouring province of Pisidia the people of Telmissus had wide fame for that skill; it was supposed instinctive and hereditary in men and women of particular families. Going thither, as he approached the first village of the Telmissian territory, he saw a girl drawing water at a spring; and making some inquiry, which led to further conversation, he related the phenomenon. It happened that the girl was of a race of seers; she told him to return immediately home, and sacrifice to Jupiter the king. Satisfied so far, he remained anxious about the manner of performing the ceremony, so that it might be certainly acceptable to the deity; and the result was that he married the girl, and she accompanied him home.

Nothing important followed till a son of this match, named Midas, had attained manhood. The Phrygians then, distressed by violent civil dissensions, consulted an oracle for means to allay them. The answer was, “that a cart would bring them a king to relieve their troubles.” The assembly was already formed to receive official communication of the divine will, when Gordius and Midas arrived in their cart to attend it. Presently the notion arose and spread, that one of those in that cart must be the person intended by the oracle. Gordius was then advanced in years. Midas, who already had been extensively remarked for superior powers of both body and mind, was elected king of Phrygia. Tranquillity ensued among the people; and the cart, predesigned by heaven to bring a king the author of so much good, was, with its appendages, dedicated to the god, and placed in the citadel, where it was carefully preserved.

The yoke was fastened with a thong, formed of the bark of a cornel tree, so artificially that no eye could discover either end; and rumour was become popular of an oracle, which declared that whosoever loosened that thong would be lord of Asia. The extensive credit which this rumour had obtained, and the reported failure of the attempts of many great men, gave an importance to it. Alexander, in the progress of his campaign in Asia, arrived at Gordium, and of course visited the castle in which was preserved the Gordian knot. While, with many around, he was admiring it, the observation occurred that it being his purpose to become lord of Asia, he should, for the sake of popular opinion, have the credit of loosening the yoke. Some writers have reported that he cut the knot with his sword; but Aristobulus, who, as one of his generals, is likely to have been present, related that he wrested the pin from the beam, and so, taking off the yoke, said that was enough for him to be lord of Asia.

Thunder and lightning on the following night, says Arrian, confirmed the assertion that Alexander had effected what the oracle had declared was to be done only by one who should be lord of Asia. Accordingly on the morrow he performed a magnificent thanksgiving sacrifice, in acknowledgment of the favour of the gods, thus promised: a measure as full of policy as devotion.

In Cornwall are to be found enormous piles of stone, which bear the name of Ambrosian, Logan, or Rocking Stones. Structures of this kind, as they may, perhaps, reasonably be called, are of very great antiquity, being represented on medals of Tyre. They appear to have been composed of cones of rock let into the ground, with other stones adapted to their points, and so nicely balanced, that the wind could move them; and yet so ponderous, that no human force, unaided by machinery, could displace them. The figures of Apollo Didymus, on the Syrian coins, are placed sitting on the point of the cone, on which the more rude and primitive symbol of the Logan stone is found poised; and we are told, that the oracle of the god near Miletus existed before the emigration of the Ionian colonies, more than eleven hundred years before Christ.

Pliny, in his second book, relates that there was one to be seen at Harpasa in Asia, exactly answering the description of those found in Cornwall. “Lay one finger on it, and it will stir; but thrust against it with your whole body, and it will not move.” Hephæstion mentions the Gigonian stone, near the ocean, which may be moved with the stalk of an asphodel, but cannot be removed by any force. Several of these stones may be seen in the neighbourhood of Heliopolis, or Baalbeck, in Syria; and one in particular has been seen in motion by the force of the wind alone.

The famous Logan stone, commonly called Minamber, stood in the parish of Sithney, Cornwall. The top stone was so accurately poised on the one beneath, that a little child could move it; and all travellers went that way to see it; but in Cromwell’s time, one Shrubsoll, Governor of Pendennis, with much ado caused it to be undermined and thrown down, to the great grief of the country: thus its wonderful property of moving so easily to a certain point was destroyed. The cause which induced the Governor to overthrow it appears to have been that the vulgar used to resort to the place at particular times, and pay the stone more respect than was thought becoming good Christians.

A similar destructive act was committed, a few years since, by one of his majesty’s officers, the commander of a revenue cutter. His achievement had, however, not even the excuse of a mistaken religious feeling to plead in its behalf; it seems to have been prompted merely by the spirit of mischief. Having landed a part of his crew, he, with infinite labour, succeeded in overturning the most celebrated Logan stone in Cornwall. But such was the odium with which he was visited in consequence of his exploit, that he undertook the gigantic task of restoring the stone to its original situation; and he was fortunate or skilful enough to succeed. A description of the situation and magnitude of the enormous mass which he had to raise will give some idea of the difficulty which he had to encounter. It is situated “on a peninsula of granite, jutting out two hundred yards into the sea, the isthmus still exhibiting some remains of the ancient fortification of Castle Treryn. The granite which forms this peninsula is split by perpendicular and horizontal fissures into a heap of cubical or prismatic masses. The whole mass varies in height from fifty to a hundred feet; it presents on almost every side a perpendicular face to the sea, and is divided into four summits, on one of which, near the centre of the promontory, the stone in question lies. The general figure of the stone is irregular: its lower surface is not quite flat, but swells out into a slight protuberance, on which the rock is poised. It rests on a surface so inclined, that it seems as if a small alteration in its position would cause it to slide along the plane into the sea, for it is within two or three feet of the edge of the precipice. The stone is seventeen feet in length, and above thirty-two in circumference near the middle, and is estimated to weigh nearly sixty-six tons. The vibration is only in one direction, and that nearly at right angles to the length. A force of a very few pounds is sufficient to bring it into a state of vibration; even the wind blowing on its western surface, which is exposed, produces this effect in a sensible degree. The vibration continues a few seconds.”

Such immense masses being moved by means so inadequate must naturally have conveyed the idea of spontaneous motion to ignorant persons, and have persuaded them that they were animated by an emanation from the Deity or Great Spirit, and, as such, might be consulted as oracles.

It cannot be doubted that those Logan stones are druidical monuments; but it is not certain what particular use the priests made of them. Mr. Toland thinks that the Druids made the people believe that they could only be moved miraculously, and by this pretended miracle they condemned or acquitted an accused person. It is likely that some of these stones were of natural formation, and that the Druids made and consecrated others; by such pious frauds increasing their private gain, and establishing an ill-grounded authority by deluding the common people. The basins cut on the top of these stones had their part to act in these juggles; and the ruffling or quiescence of the water was to declare the wrath or testify the pleasure of the god consulted, and somehow or other to confirm the decision of the Druids.

CHAPTER III.

FALSE MESSIAHS, PROPHETS, AND MIRACLES.

The earlier species of superstitious belief are now passed away, and the remembrance of them only serves to adorn poetic fiction. In eastern countries, where the imagination is more susceptible, men have yielded a religious faith to one, the rapid extension of whose tenets, though subsequent indeed to his death, was as astonishing as the boldness and effrontery of his attempt; which may be considered without a parallel in the annals of imposture.

Mahomet, the original contriver and founder of the false religion so extensively professed in the East, has always been designated, par excellence, “The Impostor.” He was born at Mecca, in the year of our Lord 571, of the tribe of the Koreshites, the noblest and most powerful in the country. In his youth he was employed by his uncle, a merchant, as a camel-driver; and, as a term of reproach, and proof of the lowness of his origin, his enemies used to call him “The Camel-driver.” When he was once in the market-place of Bostra with his camels, it is asserted, that he was recognised by a learned monk, called Bahira, as a prophet; the monk pretended to know him by a halo of divine light around his countenance, and he hailed him with joy and veneration.

In his twenty-fifth year Mahomet married a rich widow; this raised him to affluence, and he appeared at that time to have formed the secret plan of obtaining for himself sovereign power. He assumed the character of superior sanctity, and every morning retired to a secret cave, near Mecca, where he devoted the day to prayer, abstinence, and holy meditation.

In his fortieth year, he took the title of Apostle of God, and increased his fame by perseverance, and the aid of pretended visions. He made at first but few proselytes; his enemies, who suspected his designs, and perhaps foresaw his bold and rapid strides to power, heaped on him the appellations of impostor, liar, and magician. But he overcame all opposition in promulgating his doctrine, chiefly by flattering the passions and prejudices of his nation. In a climate exposed to a burning sun, he allured the imagination, by promising as rewards, in the future state, rivers of cooling waters, shady retreats, luxurious fruits, and immaculate houris. His system of religion was given out as the command of God, and he produced occasionally various chapters, which had been copied from the archives of Heaven, and brought down to him by the Angel Gabriel; and if difficulties or doubts were started, they were quickly removed, as this obliging Angel brought down fresh revelations to support his character for sanctity. When miracles were demanded of him, in testimony of his divine mission, he said with an air of authority, that God had sent Moses and Christ with miracles, and men would not believe; therefore, he had sent him in the last place without them, and to use a sword in their stead. This communication exposed him to some danger, and he was compelled to fly from Mecca to Medina; from which period is fixed the Hegira, or flight, at which he began to propagate his doctrines by the sword. His arms were successful. In spite of some checks, he ultimately overcame or gained over all his foes, and within ten years after his flight, his authority was recognised throughout the Arabian peninsula. Among the tribes subjugated by his sword was the Jewish tribe of Khaibar. He put to death Kenana, the chief, who assumed the title of King of the Jews; and after the victory, he took up his abode in the house of a Jew, whose son, Marhab, had fallen in the contest. This circumstance nearly cost him his life. Desirous to avenge her brother, Zeinab, the sister of Marhab, put poison in a shoulder of mutton, which was served up to Mahomet. The prophet was saved by seeing one of his officers fall, who had begun before him to eat of the dish. He hastily rejected the morsel which he had taken into his own mouth; but so virulent was the poison, that his health was severely injured, and his death is thought to have been hastened by it. On being questioned as to the motive which had prompted her, Zeinab boldly replied, “I wished to discover whether you are really a prophet, in which case you could preserve yourself from the poison; and, if you were not so, I sought to deliver my country from an impostor and a tyrant.”

Mahomet died at Medina, and a fabulous tradition asserts that his body in an iron coffin, was suspended in the air, through the agency of two loadstones concealed, one in the roof, and the other beneath the floor of his mausoleum.

The success of this impostor, during his life, is not more astonishing than the extent to which his doctrines have been propagated since his death. The Koran was compiled subsequent to his decease, from chapters said to have been brought by the angel Gabriel from Heaven. It is composed of sublime truths, incredible fables, and ludicrous events; by artful interpolation he grafted on his theories such parts of the Holy Scriptures as suited his purpose, and announced himself to be that comforter which our Saviour had promised should come after him.

Mahomet was a man of ready wit, and bore all the affronts of his enemies with concealed resentment. Many artifices were had recourse to, for the purpose of delusion; it is said a bull was taught to bring him on its horns revelations, as if sent from God; and he bred up pigeons to come to his ears, and feign thereby that the Holy Ghost conversed with him. His ingenuity made him turn to his own advantage circumstances otherwise against him. He was troubled with the falling sickness, and he persuaded his followers that, during the moments of suspended animation, he accompanied the Angel Gabriel, in various journeys, borne by the celestial beast Alborak, and that ascending to the highest heavens, he was permitted to converse familiarly with the Almighty.

His first interview with the angel took place at night, when in bed; he heard a knocking at the door, and having opened it, he then saw the Angel Gabriel, with seventy-nine pairs of wings, expanded from his sides, whiter than snow, and clearer than crystal, and the celestial beast beside him. This beast he described as being between an ass and mule, as white as milk, and of extraordinary swiftness. Mahomet was most kindly embraced by the angel, who told him that he was sent to bring him unto God in heaven, where he should see strange mysteries, which were not lawful to be seen by other men, and bid him get upon the beast; but the beast having long lain idle, from the time of Christ till Mahomet, was grown so restive and skittish, that he would not stand still for Mahomet to get upon him, till at length he was forced to bribe him to it, by promising him a place in Paradise. The beast carried him to Jerusalem in the twinkling of an eye. The departed saints saluted them, and they proceeded to the oratory in the Temple; returning from the Temple they found a ladder of light ready fixed for them, which they immediately ascended, leaving the Alborak there tied to a rock till their return.

Mahomet is said to have given a dying promise to return in a thousand years, but that time being already past, his faithful followers say the period he really mentioned was two thousand, though, owing to the weakness of his voice, he could not be distinctly heard.

A pilgrimage to Mecca is thought, by devout Mahometans, to be the most efficacious means of procuring remission of sins and the enjoyments of Paradise; and even the camels[3] which go on that journey are held so sacred after their return, that many fanatical Turks, when they have seen them, destroy their eyesight by looking closely on hot bricks, desiring to see nothing profane after so sacred a spectacle.

The early leaning of the Jews towards idolatry and superstition has been recorded in terms that admit of no dispute, by their own historians. The same leaning continued to be manifest in them for many ages. Sandys, in his travels, heard of an ancient tradition current on the borders of the Red Sea, that the day on which the Jews celebrate the passover, loaves of bread, by time converted into stone, are seen to arise from that sea;[4] and are supposed to be some of the bread the Jews left in their passage.

They were sold at Grand Cairo, handsomely made up in the manner and shape of the bread, at the time in which he wrote; and this was of itself sufficient to betray the imposture.

The anxiously-expected appearance of their Messiah made the Jews very easily imposed upon by those who for interested motives chose to assume so sacred a title. Our Saviour predicted the coming of false Christs, and many have since his day appeared, though perhaps no false prophet in later days has excited a more general commotion in that nation than Sabatai Sevi.

According to the prediction of several Christian writers, who commented on the Apocalypse, the year 1666 was to prove one of wonders, and particularly of blessings to the Jews; and reports flew from place to place, of the march of multitudes of people from unknown parts in the remote deserts of Asia, supposed to be the ten tribes and a half lost for so many ages, and also that a ship had arrived in the north of Scotland, with sails and cordage of silk, navigated by mariners who spoke nothing but Hebrew; with this motto on their flag, “The twelve tribes of Israel.” These reports, agreeing thus near with former predictions, led the credulous to expect that the year would produce strange events with reference to the Jewish nation.

Thus were millions of people possessed, when Sabatai Sevi appeared at Smyrna, and proclaimed himself to the Jews as their Messiah; declaring the greatness of his approaching kingdom, and the strong hand whereby God was about to deliver them from bondage, and gather them together.

“It was strange,” says Mr. Evelyn, “to see how this fancy took, and how fast the report of Sabatai and his doctrine flew through those parts of Turkey the Jews inhabited: they were so deeply possessed of their new kingdom, and their promotion to honour, that none of them attended to business of any kind, except to prepare for a journey to Jerusalem.”

Sabatai was the son of Mordechai Sevi, an inhabitant of Smyrna, who acted as a broker to English merchants. His son, studying metaphysics, vented a new doctrine in the law; and, gaining some disciples, he attracted sufficient notice to cause his banishment from the city. During his exile he was twice married, but soon after each ceremony he obtained a divorce. At Jerusalem he married a third time. He there began to preach a reform in the law, and meeting with another Jew, named Nathan, he communicated to him his intention of proclaiming himself the Messiah, so long expected, and so much desired by the Jews.

Nathan assisted in this deceit, and as, according to the ancient prophecies, it was necessary Elias should precede the Messiah, Nathan thought no one so proper as himself to personate that prophet. Nathan, therefore, as the forerunner of the Messiah, announced to the Jews what was about to take place, and that consequently nothing but joy and triumph ought to dwell in their habitations. This delusion being once begun, many Jews really believed what they so much desired; and Nathan took courage to prophesy, that in one year from the 27th of Kislev (June), the Messiah should appear, and take from the grand signior his crown, and lead him in chains like a captive.

Sabatai meanwhile preached at Gaza repentance to the Jews, and obedience to himself and his doctrine. These novelties very much affected the Jews; and they gave themselves up to prayers, alms, and devotion. The rumour flying abroad, letters of congratulation came from all parts to Jerusalem and Gaza: and thus encouraged, Sabatai resolved to travel to Smyrna, and thence to Constantinople, the capital city, where the principal work was to be performed.

All was now expectation among the Jews; no trade was followed, and every one imagined that daily provisions, riches, and honour, were to descend upon him miraculously. Many fasted so long that they were famished to death; others buried themselves in their gardens up to the neck; but the most common mortification was to prick their backs and sides with thorns, and then give themselves thirty-nine lashes.

To avoid the necessity of business, which was even made a fineable offence, the rich were taxed to support the poor; and, lest the Messiah should accuse them of neglecting ancient precepts, particularly that to increase and multiply, they married together children of ten years and under. Without respect to riches or poverty, to the number of six or seven hundred couples were indiscriminately joined: but on better and cooler thoughts, after the deceit was discovered, or expectation grew cold, these children were divorced or separated by mutual consent.

At Smyrna, Sabatai was well received by the common Jews, but not so by the chochams or doctors of the law, who gave no credence to his pretensions. Yet Sabatai, bringing testimonials of his sanctity, holy life, wisdom, and gift of prophecy, so deeply fixed himself in the hearts of the generality, that he took courage to dispute with the grand chocham. Arguments grew so strong, and language so hot, between the disputants, that the Jews who espoused Sabatai’s doctrine appeared in great numbers before the Cadi of Smyrna, in justification of him. Sabatai thus gained ground, whilst the grand chocham in like proportion lost it, as well as the affection and obedience of his people, and ultimately he was displaced.

No invitation was now ever made by the Jews, or marriage ceremony solemnized, where Sabatai was not present, accompanied by a multitude of followers; and the streets were covered with carpets or fine cloths for him to tread upon, which the pretended humility of this Pharisee stooped to turn aside. Many of his followers became prophetic; and infants, who could scarcely stammer a syllable to their mothers, could pronounce and repeat his name. There were still, however, numbers bold enough to dispute his mission, and to proclaim him an impostor.

Sabatai then proceeded with great presumption to an election of princes, who were to govern the Israelites during their march to the Holy Land. Miracles were thought necessary for the confirmation of the Jews in their faith; and it was pretended that on one occasion a pillar of fire was seen between Sabatai and the cadi: though but few were said to have seen it, it speedily became the general belief, and Sabatai returned triumphant to his house, fixed in the hearts of all his people. He then prepared for his journey to Constantinople, where his great work was to be accomplished: but, to avoid the confusion of his numerous followers, he went by sea with a small party, and was detained thirty-nine days by contrary winds. His followers, having arrived overland before him, awaited his coming with great anxiety. Having heard of the disorder and madness that had spread among the Jews, and fearing the consequences, the vizir sent a boat to arrest Sabatai, and he was brought ashore a prisoner, and committed to the darkest dungeon, to await his sentence.

Undiscouraged by this event, the Jews were rather confirmed in their belief; and visited him with the same ceremony and respect, as if exalted on the throne of Israel. Sabatai was kept a prisoner two months, and then removed to the castle of Abydos, where he was so much sought after by the Jews, that the Turks demanded five or ten dollars for the admission of each proselyte. At his leisure in this castle, he composed a new mode of worship.

The Jews now only awaited the personal appearance of Elias, previous to the glorious consummation. There is a superstition among them, that Elias is invisibly present in their families, and they generally spread a table for him, to which they invite poor people; leaving the chief seat for the Lord Elias, who they believe partakes of the entertainment with gratitude. On one occasion, at the ceremony of circumcision, Sabatai took advantage of this credulity, for he exhorted the parents to wait awhile, and, after an interval of half an hour, he ordered them to proceed. The reason he gave for this delay was, that Elias had not at first taken the seat prepared for him, and therefore he had waited till he saw him sit down.

Having had the history of the whole affair laid before him, the grand signior sent for Sabatai to Adrianople. On receiving the summons, the pseudo-Messiah appeared to be much dejected, and to have lost that courage which he formerly showed in the synagogues. The grand signior would not be satisfied without a miracle any more than the Jews; but he wisely resolved that it should be one of his own choosing. He ordered that Sabatai should be stripped naked, and set up as a mark for the dexterous archers of the sultan to shoot at, and, if it was found that his skin was arrow-proof, he would then believe him to be the Messiah. Not having faith enough in himself to stand so sharp a trial, Sabatai renounced all title to kingdoms and governments, alleging that he was merely an ordinary chocham. Not satisfied with this, the grand signior declared that the treason of the Jew was only to be expiated by a conversion to Mahometanism, which if he refused, a stake was ready at the gate of the seraglio, on which to impale him. Sabatai replied, with much cheerfulness, that he was contented to turn Turk; and that not of force, but choice, he having been a long time desirous of so glorious a profession.

When the Jews received intelligence of Sabatai’s apostacy, and found that all their insane hopes were completely blighted, they were filled with consternation and shame. The news quickly spread all over Turkey, and they became so much the common derision of all the unbelievers, that, for a long time, they were overcome with confusion and dejection of spirit.

Of subsequent pretenders to the sacred character of the Messiah, it must suffice to mention two; the one of them a German, the other an English subject.

The German, whose name was Hans Rosenfeld, was a gamekeeper. The scene of his impious or insane pretensions was Prussia and the neighbouring states. He taught that Christianity was a deception, and that its priests were impostors. Having thus summarily disposed of spiritual matters, he proceeded to meddle with temporal in a manner which was not a little dangerous under a despotic government. Frederick the Great, who was then on the throne, he declared to be the devil; and, as it was not fit that the devil should reign, Rosenfeld made known that he intended to depose him. Having accomplished this difficult feat, he was to rule the world, at the head of a council of twenty-four elders. The seven seals were then to be opened. In his choice of the angels who were to open the seals, he took care to have an eye to his own pleasure and interest. He demanded from his followers seven beautiful girls, who were to fill the important office; but that, in the mean while, the office might not be a sinecure, they held the place of mistresses to him, and maintained him by their labour.

Rosenfeld was suffered to go on thus for twenty years, with occasionally a short imprisonment, and he still continued to find dupes. He might, perhaps, have gone to his grave without receiving any serious check, had he not been overthrown, though unintentionally, by one of his own partisans. This man, who had resigned three of his daughters to the impostor, was tired of waiting so long for his promised share of the good things which the pseudo-Messiah was to dispense; it was not his faith, it was only his patience, that was exhausted. To quicken the movements of Rosenfeld, he hit upon a rare expedient. As, according to his creed, the king was the devil, he went to him for the purpose of provoking the monarch to play the devil, by acting in such a manner as should compel the impostor to exert immediately his supernatural powers. On this provocation, Frederick did act, and with effect. Rosenfeld was ordered to be tried; the trial took place in 1782, and the tribunal sentenced him to be whipped, and imprisoned for life at Spandau. Against this sentence he twice appealed, but it was finally executed.

The English claimant of divine honours was Richard Brothers. He was born at Placentia, in Newfoundland, and had served in the navy, but resigned his commission, because, to use his own words, he “conceived the military life to be totally repugnant to the duties of Christianity, and he could not conscientiously receive the wages of plunder, bloodshed, and murder.” This step reduced him to great poverty, and he appears to have suffered much in consequence. His mind was already shaken, and his privations and solitary reflections seem at length to have entirely overthrown it. The first instance of his madness appears to have been his belief that he could restore sight to the blind. He next began to see visions and to prophesy, and soon became persuaded that he was commissioned by Heaven to lead back the Jews to Palestine. It was in the latter part of 1794 that he announced, through the medium of the press, his high destiny. His rhapsody bore the title of “A revealed Knowledge of the Prophecies and Times. Book the First. Wrote under the direction of the Lord God, and published by his sacred command; it being the first sign of warning for the benefit of all nations. Containing, with other great and remarkable things, not revealed to any other person on earth, the restoration of the Hebrews to Jerusalem, by the year of 1798: under their revealed prince and prophet.” A second part speedily followed, which purported to relate “particularly to the present time, the present war, and the prophecy now fulfilling: containing, with other great and remarkable things, not revealed to any other person on earth, the sudden and perpetual fall of the Turkish, German, and Russian Empires.” Among many similar flights, in this second part, was one which described visions revealing to him the intended destruction of London, and claimed for the prophet the merit of having saved the city, by his intercession with the Deity.

Though every page of his writings betrayed the melancholy state of the unfortunate man’s mind, such is the infatuation of human beings, that he speedily gained a multitude of partisans, who placed implicit faith in the divine nature of his mission. Nor were his followers found only in the humble and unenlightened classes of society. Strange as it may appear, he was firmly believed in by men of talent and education. Among his most devoted disciples were Sharpe, the celebrated engraver, whom we shall soon see clinging to Joanna Southcott; and Mr. Halhed, a profound scholar, a man of great wit and acuteness, and a member of the House of Commons. The latter gave to the world various pamphlets, strongly asserting the prophetic mission of Brothers, and actually made in the House a motion in favour of the prince of the Jews. Numerous pamphlets were also published by members of the new sect.

Brothers was now conveyed to a madhouse at Islington; but he continued to see visions, and to pour forth his incoherencies in print. One of his productions, while he was in this asylum, was a letter, of two hundred pages, to “Miss Cott, the recorded daughter of King David, and future Queen of the Hebrews. With an Address to the Members of his Britannic Majesty’s Council.” The lady to whom his letter was addressed had been an inmate of the same receptacle with himself, and he became so enamoured, that he discovered her to be “the recorded daughter of both David and Solomon,” and his spouse, “by divine ordinance.” Brothers was subsequently removed to Bedlam, where he resided till his decease, which did not take place for several years.

Among the most mischievous of the pretenders to prophetical inspiration may be reckoned Thomas Muncer, and his companions, Storck, Stubner, Cellarius, Thomas, and several others, contemporaries of Luther, from whom sprang the sect of the Anabaptists. Eighty-four of them assumed the character of twelve apostles and seventy-two disciples. “They state wonderful things respecting themselves,” says Melancthon, in a letter to the Elector of Saxony; “namely, that they are sent to instruct mankind by the clear voice of God; that they verily hold converse with God, see future things, and, in short, are altogether prophetical and apostolical men.” Muncer was, of them all, the one who possessed the highest portion of talents and eloquence, and chiefly by his exertions a spirit of insurrection was excited among the peasantry. Expelled from Saxony, he found a retreat at Alstadt, in Thuringia, where the people listened to his revelations, gave him the chief authority in the place, and proceeded to establish that community of goods which was one of his doctrines. The war of the peasants had by this time broken out, but Muncer hesitated to place himself at their head. The exhortations of Pfeifer, another impostor, of a more daring spirit, and who pretended to have seen visions predictive of success, at length induced him to take the field. His force was, however, speedily attacked, near Frankhuysen, by the army of the allied princes, and, in spite of the courage and eloquence which he displayed, it was utterly defeated. Muncer escaped for the moment, but speedily fell into the hands of his enemies, and, after having been twice tortured, was beheaded. The same fate befell Pfeifer and some of his associates. Of the unfortunate peasants, who had been driven to arms by oppression, still more than by fanaticism, several thousands perished.

Nine years afterwards, consequences equally disastrous were produced by fanatical leaders of the same sect. In 1534, John Matthias of Haarlem, and John Boccold, who, from his birthplace being Leyden, is generally known as John of Leyden, at the head of their followers, among the most conspicuous of whom were Knipperdolling, and Bernard Rothman, a celebrated preacher, succeeded in making themselves masters of the city of Munster. Though Matthias was originally a baker, and the latter a journeyman tailor, they were unquestionably men of great courage and ability. As soon as they were in possession of the place, the authority was assumed by Matthias, and equality and a community of goods were established, and the name of Munster was changed to that of Mount Sion. The city was soon besieged by its bishop, Count Waldeck. Matthias, who had hitherto displayed considerable skill in his military preparations, now took a step which proved that his reason had wholly deserted him. He determined, in imitation of Gideon, to go forth with only thirty men, and overthrow the besieging host. Of course he and his associates perished.