All books 24glo.com/book/

Read online, download free ebook PDF, ePUB, MOBI docx txt AZW3

Munroe, Kirk. Prince Dusty. A Story of the Oil Regions.

Originally published: 1891

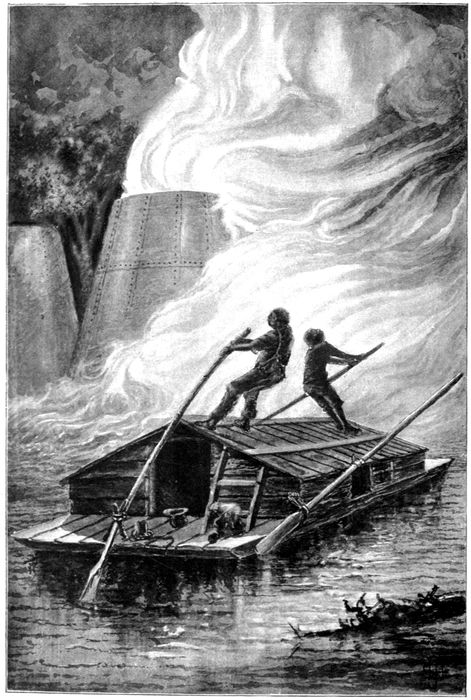

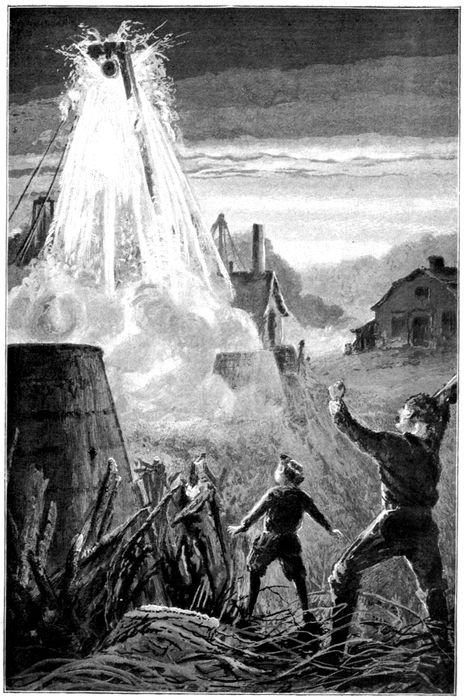

ONE OF THE GREAT OIL TANKS HAD BEEN STRUCK BY LIGHTNING, AND NOW A RAGING, ROARING MASS OF FLAME SHOT UP.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | |

|---|---|

| I.— | A Prince and Princess Go in Search of Adventures |

| II.— | A Present from a Fairy GodMother |

| III.— | Brace Barlow the “Moonlighter” |

| IV.— | A Torpedo Man’s Peril |

| V.— | Arthur and His Cousins |

| VI.— | A Gallant Rescue and Its Reward |

| VII.— | Uncle Phin’s Plan |

| VIII.— | Awakened at Midnight |

| IX.— | A Hurried Flight |

| X.— | On Board the Ark |

| XI.— | Uncle Phin’s Danger |

| XII.— | A Torrent of Flame |

| XIII.— | How the Ark was Saved |

| XIV.— | A Camp of Tramps |

| XV.— | Arthur’s Fight to Save Rusty |

| XVI.— | The Meaning of Some Queer Signs |

| XVII.— | Pleasant Driftings |

| XVIII.— | The Ark is Stolen |

| XIX.— | Penniless Wanderers in a Strange City |

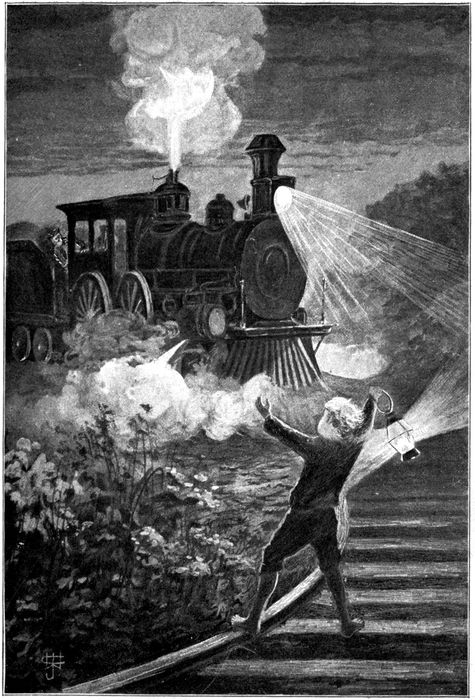

| XX.— | A Railroad Experience |

| XXI.— | Carried Off in a Freight Car |

| XXII.— | Saving the Keystone Express |

| XXIII.— | Crossing the Alleghanies |

| XXIV.— | A Brave Struggle with Poverty |

| XXV.— | Finding a Home |

| XXVI.— | Colonel Dale of Dalecourt |

| XXVII.— | A “Genuine Chump” |

| XXVIII.— | A Few Facts Concerning Petroleum |

| XXIX.— | Locating an Oil Well |

| XXX.— | The Dale-Dustin Mystery |

| XXXI.— | A Bitter Disappointment |

| XXXII.— | Shooting a “Duster” |

| XXXIII.— | Saved by the Sign of the Tramp |

| XXXIV.— | An Oil Scout Outwitted |

| XXXV.— | Developing an Oil Region |

| XXXVI.— | Arthur Remembers His Friends |

CHAPTER I.

A PRINCE AND PRINCESS GO IN SEARCH OF ADVENTURES.

Twelve-year-old Arthur Dale Dustin did not look the least bit like a Prince, sitting perched on the topmost rail of the zig-zag fence that bright September afternoon. As he dangled his bare brown legs idly, he wistfully watched his cousins at the play in which they would not allow him to join. He loved to play as dearly as any other boy; but somehow or other he was always left out of their games by the boisterous crew of little Dustins whom he called cousins. He tried his best to like what they liked, and to be one with them; but something always seemed to happen to prevent.

Once when they all went to see the well that his uncle, John Dustin, was drilling, deep down into the ground, with the hope of striking petroleum, they found the men away, and, for a few minutes, had the place to themselves. Thereupon Cousin Dick, who was two years older than Arthur, climbed up the derrick, and, watching his chance, sprang on the end of the great walking beam, that was working slowly up and down with ponderous strokes. Here he rode on the back of his mighty wooden steed for a few seconds, while the other children shouted and clapped their hands with admiration.

Then Dick came down and dared Arthur to perform the same feat; but the boy held back. He was not afraid, not a bit of it; and even if he had been he would gladly have done anything Dick dared do, merely to win his good-will and that of the others. But his Uncle John had forbidden them even to go near the derrick or the engine unless he was there to look after them. The others seemed to have forgotten this; but Arthur remembered it, and so refused to ride on the walking beam because it would be an act of disobedience. Then Cousin Dick sneered at him, and called him a “’Fraid-cat,” and all the others, except tender-hearted, freckle-faced little Cynthia, took up the cry and shouted, “’Fraid-cat! ’Fraid-cat!” as they crowded around him and pushed him into the derrick.

Just then Uncle John returned and the others ran away, leaving poor Arthur, looking very confused and red in the face, standing in the middle of the derrick floor. Then, when his uncle in a stern voice asked him what he was doing in that place which he had been strictly forbidden to enter, Arthur hung his head and would not say anything; for he was too brave a lad to be a “tell-tale,” and too honest to tell a lie. So his Uncle John said that he was a naughty boy who had led the other children into mischief, and that he might go right home and get into bed, and stay there for the rest of the day as a punishment.

Poor Arthur obeyed; and, as he walked slowly toward the only place in the world he could call his home, great tears rolled down his cheeks. When the other children, who were hiding in the bushes, saw them they called out, “Cry-baby! Cry-baby!” Only little Cynthia ran out and put her arm about his neck and said she was sorry; but Dick pulled her roughly away.

Another time when Cynthia asked Arthur to build a house for her dolls, under the roots of a great tree that had blown down just on the edge of the woods back of the house, he, being an obliging little soul, consented at once to do so. Under the huge mass of roots and earth they played happily enough at making believe it was a cave, and Cynthia was radiant with delight over the beautiful time they were having. For a little while Arthur experienced the novel feeling of being perfectly happy. Then, all of a sudden, a shower of earth and gravel came rattling down on them from above, and with it came a mocking chorus of “Girl-boy! Girl-boy! Look at the girl-boy playing with dolls!” and little Cynthia began to cry over the ruin of her beautiful baby-house.

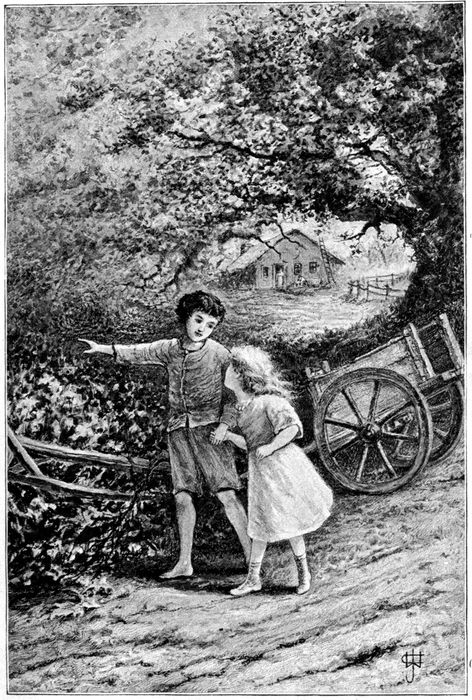

PRINCE DUSTY AND CYNTHIA SET OUT ON THEIR ADVENTURES.

Upon this, with a quick blaze of indignation, Arthur picked up a bit of stick and flung it with all his strength at the tormentors who had brought tears to his little cousin’s eyes. It was aimed at nobody in particular; but it happened to strike Dick on the cheek and make a slight cut, from which the blood flowed. Thereupon the big boy ran crying home to his mother, and told her that Arthur had struck him with a stick, in proof of which story he showed his bloody face. Then Mrs. Dustin, who always acted upon the impulse of the moment, took down the apple switch from over the mantel-piece and gave her nephew a whipping, which she said would be a lesson to him. Poor little Cynthia tried to explain how it had all happened; but her mother had no time to listen, and only told her and the other children to come away from the bad boy, and not go near him again that day.

Some days after this, when all the others had gone on a fishing expedition, upon which they had refused to let Arthur and Cynthia accompany them, the boy proposed a beautiful plan to his little cousin. He remembered the fairy tales his own dear mother used to read to him, and now he said:

“Let us make believe we are a Prince and Princess, Cynthia, and go out into the world in search of adventures.”

Cynthia had not the remotest idea of what was meant by “adventures”; but she was willing to agree to anything that Arthur might propose.

So the two children set forth, and nobody noticed them as they went out of the front gate and walked, hand in hand, down the dusty road.

They had not gone far before they discovered a poor little robin just learning to fly, that had fallen into a ditch by the roadside, where in a few moments more he would have been drowned. Of course they rescued him, and, while the old mother and father birds flew about them uttering cries of distress and begging them not to hurt their baby, Cynthia dried his wings and carefully wiped the mud from his downy feathers with her pinafore. Then Arthur climbed over a fence and gently placed the little trembling thing down in the soft grass on the other side.

Next they found a yellow butterfly, whose pretty wings were all tangled in a spider’s web. Of course they set him free, and had the pleasure of seeing him flutter joyously away. Arthur said these were beautiful adventures, and both the children looked eagerly forward to finding some more; but they walked nearly a mile, and were becoming very hot and tired, before they met with another.

All of a sudden, as they were passing a cottage by the roadside, they were startled by a deep, loud bark, and turning they saw a big Newfoundland dog bound over the front fence, and come dashing directly toward them. Now, while Arthur was very fond of dogs that he was acquainted with, he was also very much afraid of strange dogs, especially big ones; and his first impulse upon this occasion was to run away. Then he remembered that he was a Prince, and that princes were always brave. So he told Cynthia to run as fast as she could, and hide in the bushes. As she did this the brave little fellow turned a bold front, though he was trembling in every limb, toward the enemy. The next instant the big dog sprang upon him, threw him down, rolled him in the dust, and then stood over him wagging a bushy tail, and barking with delight at what he had done.

CHAPTER II.

A PRESENT FROM A FAIRY GODMOTHER.

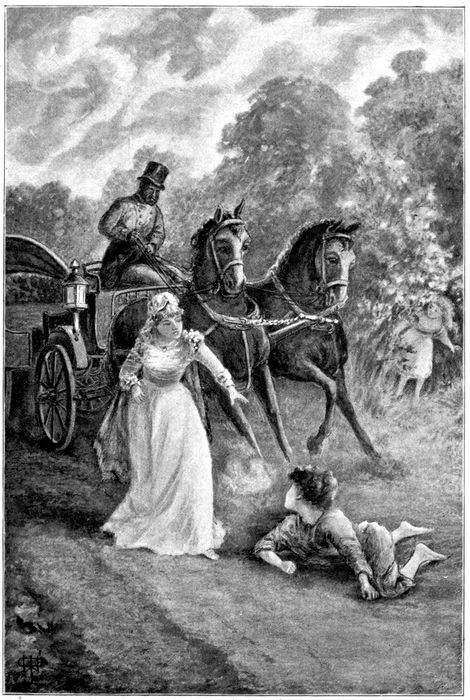

Arthur, who thought he was certainly to be killed, shut his eyes, and for nearly a minute lay perfectly still. He opened them on hearing a trampling of hoofs, a jingling of harness, and a loud “Whoa.” Then, no longer seeing the dog, he quickly scrambled to his feet. He was right under the noses of a pair of splendid horses, and behind them was a fine carriage, from which a beautiful lady was just stepping.

“Why, little boy,” she said, as she took Arthur’s hand and led him away from in front of the horses, “don’t you know that you came very near being run over? and that it is dangerous to be playing out here in the middle of the road? Now run into the house, and ask your mother to brush your clothes, and don’t ever do so again.”

PRINCE DUSTY AND HIS FAIRY GODMOTHER.

“But I don’t live here,” said Arthur, lifting his dust-covered little face to the gracious one bent down to him. “I live a long way off, and I’m a Prince, and Cynthia is a Princess, and we were looking for adventures, when a big dog knocked me down; but he didn’t hurt Cynthia, because I defended her, the same as princes do in the stories my own mamma used to read to me.”

“So you are a Prince, are you?” laughed the lady; “then you must be ‘Prince Dusty.’ Well, if you will get into my carriage, and show me the way, I will take you home to your castle. But where is your Princess? What did you say her name was?”

“It is Cynthia,” replied Arthur, “and there she comes now.”

As he spoke, poor, terrified little Cynthia came timidly out from the bushes where she had been hiding, and crying with fright, for the last three minutes.

Then the beautiful lady took them both into her carriage, and ordered the coachman to drive on, while she soothed and comforted the children, and wiped Arthur’s dusty face with her own embroidered handkerchief.

She looked curiously at him when he told her that his name was Arthur Dale Dustin, that his dearest mamma and papa were dead, and that he used to live in New York, but that now he lived with Cynthia’s father and mother, who were his Uncle John and Aunt Nancy. She asked him several questions about himself; but always seemed to forget his name and only called him “Prince Dusty.”

When they reached the Dustin house she kissed both the children good-bye, and gave Arthur a beautiful copy of Hans Christian Andersen’s “Fairy Tales,” that she had in the carriage with her. On the fly-leaf she wrote, with a tiny gold pencil that hung from her watch-chain: “To Prince Dusty from his Fairy Godmother.” Then she said she must hurry on, and drove away, leaving the children standing by the roadside and staring after the carriage so long as the faintest cloud of dust from its wheels was visible.

As they turned slowly into the front gate, and walked toward the house, Arthur drew a long breath and said: “Cynthia, that is the very most beautiful adventure I ever heard of. It’s beautifuller even than the stories my own mamma used to tell, and I’ve got this lovely book to show that it is all true.”

Poor Arthur was not allowed to enjoy the possession of his book very long, for his Aunt Nancy, who had been alarmed at the children’s disappearance, and now gave them only bread and water for their dinner, took it from him, and laid it on a high shelf, saying that it was altogether too handsome a book for a little boy to have.

Arthur begged, and pleaded with tears in his eyes, that he might be allowed to keep his book, claiming justly that it was his very own, and had been given to him to do as he pleased with; but all to no purpose. His Aunt Nancy only said that she would give it to him when the proper time came; and then, adding that she was too busy now to be bothered with him, she bade him get out of the house, and not let her see him again before sundown.

So the sensitive little chap walked slowly away, trying in vain to choke back the indignant sobs that would persist in making themselves heard, and feeling very bitterly the injustice of his Aunt Nancy’s action. He longed for sympathy in this time of trial, and for some friendly ear into which he might pour his griefs. Even Cynthia’s company was denied him, for she was seated in the kitchen under her mother’s watchful eye, taking slow, awkward stitches in the patchwork, a square of which was her allotted task for each day.

“I’ll find Uncle Phin,” said Arthur to himself, “and tell him all about it, and perhaps he will somehow find a way to get my book again, and then I’ll ask him to take me away from here, to some place where I can keep it always.”

Somewhat cheered by having a definite purpose in view, the forlorn little fellow started across the fields toward a distant wood-lot, in which he knew his sympathizing old friend and adviser was at work.

Uncle Phin was a white-headed, simple-hearted, old negro, who, some years before, had been a slave belonging to Colonel Arthur Dale, of Dalecourt, Virginia. He had been the constant attendant, in her daily horseback rides, of the Colonel’s only daughter, the lovely Virginia Dale, to whom her father had formally presented him, as a birthday gift, when she was fifteen years old.

Three years later the spirited girl, refusing to marry the man whom her father had selected for her, ran away with Richard Dustin, a young Northerner recently graduated from a New England university, who had accepted a professorship in one of the Virginia colleges. This marriage proved so terrible a disappointment to her father that, in his anger, he declared he would never receive a communication from her, nor see her again, and he never did. The young couple, accompanied by the faithful Uncle Phin, went to New York. There their only child, a boy, named Arthur Dale after the grandfather who refused to recognize him, was born, and there they lived in the greatest happiness until the child was nearly eleven years old. Then the beautiful young mother died, leaving Richard Dustin utterly heartbroken. Soon afterward he removed with his idolized boy and Uncle Phin, who had filled the position of nurse and constant protector to Arthur from infancy, to the home of his childhood, a little rocky farm in Northwestern Pennsylvania.

He had but one relative in the world, a brother, who lived near one of the mushroom-like towns that sprang up during the early days of petroleum. When, a year after the death of his wife, Richard Dustin was also laid in the grave, it was in the family of this brother, John Dustin, that Arthur and Uncle Phin found a home.

Richard Dustin left no property save the rocky farm that was too poor even to support a mortgage. As his brother John had a large family, the new burdens now thrust upon him were not very warmly welcomed. In fact Mrs. Dustin strongly urged her husband not to receive them. She was Arthur’s Aunt Nancy, a hard, unsympathetic, overworked woman, who grudged every morsel of food that the new-comers ate, and seemed to consider that everything given to Arthur was just so much stolen from her own children.

Uncle Phin, it is true, worked faithfully to do what he could toward earning the bread eaten by himself and his “lil Marse,” as he persisted in calling Arthur, but he was old and feeble, and the best that he could do did not amount to much. The scanty, but neat, city-made wardrobe that Arthur brought with him to his new home, had not been replenished by a single garment, and now the boy’s clothes were shabby and outgrown to such a degree, that his mother’s heart would have ached could she have seen him.

Although he was a thoughtful, imaginative child, he was remarkably strong and active for his age. He had learned to read and write at his mother’s knee, and his father had, during the last year of his life, found his only pleasure in planning and directing the boy’s education. Arthur was therefore as far in advance of his cousins in this respect as he was in refinement and ideas of honor. He was so very different from them that, though he tried hard to love them and make them love him, they, with the exception of little Cynthia, to whom he was an ideal of perfection, united in cordially disliking him.

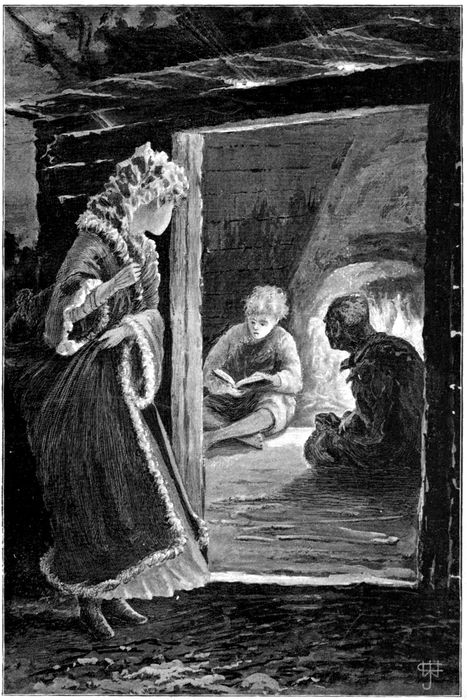

This dislike was clearly shown, and resulted in many a heartache and many an unjust punishment to the lonely orphan boy. Many a night he slipped from his little cot bed in the back shed, and creeping to where Uncle Phin slept on a hay-mow in the barn, poured his troubles with bitter tears into the sympathetic ears of the old negro.

Then the faithful soul would open wide his arms, and nestling the fair head of his “lil Marse” against his broad bosom, would soothe and comfort him with gentle croonings and quaint quavering plantation melodies. His singing was always accompanied by a slow rocking motion of the body, and finally the blue, tear-swollen eyes would close, and the boy would drop into a sleep full of beautiful dreams, in which he always saw his own dear father and mother. Then Uncle Phin’s frosted head would droop lower and lower, until he too was asleep and dreaming of his long ago cabin home under the magnolia trees of old Virginia. Thus these two would comfort each other until morning.

Now, choking with a sense of injustice and wrong at the hands of his Aunt Nancy, little Prince Dusty fled across the fields in search of this friend. He was filled with the determination to beg Uncle Phin to take him away from that hated place, to some other where they might live happily together for always and always.

CHAPTER III.

BRACE BARLOW THE MOONLIGHTER.

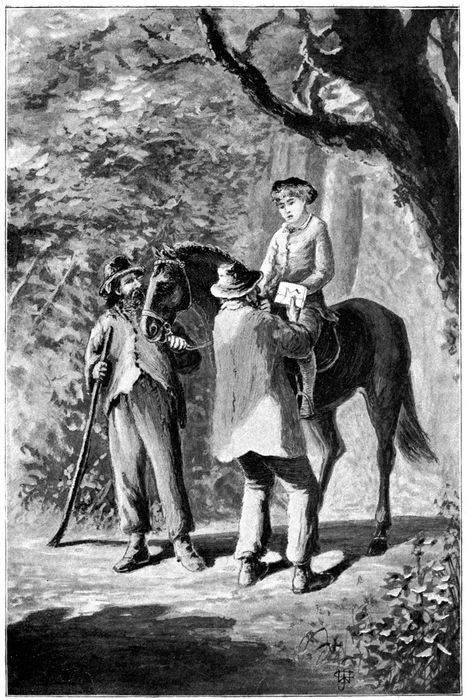

Besides Uncle Phin and Cynthia, Arthur had one other friend whom he seldom saw now, but whom he was always glad to meet. This was Brace Barlow, a stalwart, good-natured, young fellow, about twenty-five years old, who seemed so big and strong to the little boy, that the latter called him his “dear giant.” He worked for Arthur’s uncle when the boy first came to live with the Dustins, and had immediately taken a great fancy to the gentle little fellow. He taught Arthur to ride horseback, to drive a team, and to swim, and was always ready to tell him stories of adventures in the oil region. Besides these things, he took pains patiently to explain where the oil came from, and how wells were drilled, deep down into the earth to its hiding-places.

Some months before the time with which this story opens, Brace Barlow left Mr. Dustin’s employ, and, much to Arthur’s dismay, became a “moonlighter.”

Now to understand what a “moonlighter” is, one must know at least as much as Arthur did about oil wells. They are holes about the size of an ordinary stove-pipe, bored, by means of immensely heavy iron drills, hundreds and sometimes thousands of feet into the earth, until they reach the layer of porous sandstone that holds the oil, just as a sponge holds water.

With the oil in this sandstone are vast quantities of gas, that exert an enormous pressure upon it; and the moment an opening is made to where it is, this gas forces the oil to the surface, often driving it forth in great spurts and fountain-like jets. Such a well is called a “gusher,” and from it the oil flows for days, weeks, and sometimes for years. After a while, however, the supply of oil or gas, or both, becomes exhausted, so that the stream no longer rises above the mouth of the well. Then a pump is used, and by means of it the oil is pumped up, just as water is from an ordinary well. But the supply of oil always decreases, until, by and by, the pump no longer brings it up in paying quantities.

For some years after the discovery of oil, these exhausted wells were abandoned, and their owners sunk new ones in other places. At length, however, a wise man who had studied the situation very carefully, concluded that if, by any means, the oil-bearing rock could be shattered for a considerable distance around the bottom of these old wells, the flow of oil might be increased, and it might again be produced from them in paying quantities. So he invented a torpedo that could be exploded at any required depth in a well. It was simply a long tin tube, closed at the lower end, and filled with nitro-glycerine. This is one of the most terrible explosives ever discovered; and though it is only ordinary sweet glycerine, such as is used for chapped faces and hands, mixed with nitric acid, it is ten times more powerful than gunpowder, and explodes upon receiving a very slight shock or blow.

A torpedo of this kind, lowered to the bottom of an oil well, and exploded by means of a sharp-pointed iron weight dropped upon it, shatters a large area of oil-bearing rock, and the oil or gas, comes rushing to the surface as when the well was first opened. This operation is called “shooting a well”; the lowering of a torpedo into position, a thousand feet or more below the surface of the earth, is called “placing a shot,” and the men who undertake this dangerous business are called “torpedo men” or “well-shooters.”

The person who invented this process of well-shooting, and obtained a patent on it, charged so much for the use of his torpedoes that to shoot a well was an expensive undertaking. Many oil producers thought they could not afford it, or that their exhausted wells were not worth the further expenditure of so much money. Under these circumstances a class of reckless, daring fellows sprang into existence, who made a business of manufacturing torpedoes, and secretly shooting wells without paying the inventor the royalty to which his patent entitled him. Thus they were able to do the work much more cheaply than the regular torpedo men, and a great number of well owners were willing to employ them for the sake of what money they would thus save.

As these men generally worked at night they were called “moonlighters,” and many thrilling tales of the desperate risks run by them, are still told in the oil regions. The inventor of the torpedo, who was the only man having a legal right to use it, was of course most anxious to detect and punish these “moonlighters,” and for this purpose he employed a number of spies. These spies, or detectives, were generally mounted on fleet horses, and whenever they discovered a “moonlighter” driving along the lonely roads, with his load of nitro-glycerine, they gave chase to him. Then he would whip up his spirited team, and drive away at full speed, reckless of consequences, and only intent upon escaping from his pursuers.

Thus it often happened that people sleeping in the vicinity of those quiet mountain roads were awakened at night by the sound of galloping horses, the rattle of a light wagon, and the shouts of its pursuers. They would hold their breath and wait in anxious suspense until the sounds died away, happy if they did not hear the awful roar of an explosion, that meant instant death to all who were anywhere near that ill-fated wagon.

When it is remembered that such an explosion could be caused by the breaking of a wheel, the upsetting of the wagon, or even its sudden striking against a rock or stump, and that such an accident would result in the instantaneous and complete disappearance of men, horses, wagon, and everything within reach of the awful stuff, it will be understood what terrible risks the “moonlighters” ran in pursuit of their illegal business, and what reckless men they were. As the patent on oil-well torpedoes expired some years ago, and anybody can now use them who chooses to do so, there are no longer any “moonlighters,” but at the time of this story they were numerous, and Arthur’s friend, Brace Barlow, was one of the most daring of them all.

To have his “dear giant” engage in a pursuit at once so wrong and so dangerous was a great grief to the honest, loving little soul, and at every opportunity he pleaded with Brace to give it up. But the young man would only laugh, saying that he had as much right to shoot wells and risk his life as anybody else, and that it was the easiest way of making money he knew of.

At length, however, about daylight one morning, he came to the Dustin house, bruised, bleeding, and with an awe-stricken look on his usually merry face. Waking his little friend, he said he had come to tell him that his moonlighting days were over, and that hereafter he was to be an honest well-shooter, in the service of the rightful owner of the torpedo patent.

“Oh, I am so glad!” cried the boy, “only I wish you would work at something else, and never touch the awful glycerine again.”

“I can’t give it up entirely, little one,” replied Brace. “Its very danger makes it exciting, and any other life would seem tame after it.”

“Well,” said Arthur, “if you must be one, I am glad you are going to be an honest torpedo man. But, ‘dear giant,’ are you hurt? What makes you look so queer?”

Then Brace told him that about an hour before, he had been driving quietly along, with fifty quarts of nitro-glycerine stowed snugly under his buggy seat, toward a well that he was to shoot at daylight, when the sound of galloping hoofs gave warning that a detective was on his track. He instantly whipped up his horses, and, as they sprang forward, his light buggy was nearly upset by striking some obstacle, and he was thrown to the ground with such force as to be partially stunned. As he lay there the detective dashed past without noticing him, and overtaking the runaway team a minute later probably tried to stop them. They must have swerved to one side, the buggy had undoubtedly been upset, and a terrific explosion instantly followed. When Brace reached the spot no trace of man, horses, or wagon, was to be found, and only a great hole in the ground marked the scene of the catastrophe.

The boy shuddered as he listened to this story, and for days afterward his sunny face was clouded by its memory. Still he found some comfort in reflecting that nothing less than some such terrible lesson would have made an honest torpedo man of his dear “moonlighter,” with whom, from that time forward, his friendship became stronger than ever.

CHAPTER IV.

A TORPEDO MAN’S PERIL.

On the day that Arthur played at being a Prince, and was on his way to unfold the sad result of that experience to Uncle Phin, he met Brace Barlow driving out of an old wood road that led to his nitro-glycerine magazine, hidden in the loneliest depths of the forest.

At sight of his little friend, Brace reined in his horses and stopped for a moment’s chat with him.

In spite of the young man’s warning that he had a load of the “stuff” under the seat, Arthur ran forward and clambered up into the wagon beside him.

“Oh, I am so glad to see you, ‘dear giant’!” he began impulsively, “because——” Here he paused.

He had been about to pour into this friend’s ear all his troubles, and make a complaint against his Aunt Nancy; but it suddenly occurred to him that by so doing he would be only acting the part of a tale-bearer, which his father had taught him most heartily to despise. Telling things to Uncle Phin was different. He was quite certain that Brace could not help him in his present trouble, and so, when the latter asked with a smile, “Because what, little one?” he answered:

“Because I love you, and I am always glad to see the people I love. Are you going to shoot a well? Can’t I go with you? Aunt Nancy says I am to stay out of her sight until sunset, and the boys have gone fishing, and Cynthia’s doing her patchwork, and I haven’t a single thing to do. Please let me go.”

“Well, I don’t know,” replied Brace Barlow, reflectively. “I don’t suppose there is really any danger; still——”

“Danger!” exclaimed Prince Dusty, scornfully. “Do you suppose I am any more afraid of danger than you are, even if you are a great, big man and I am only a little boy? Well, I’m not. Your old glycerine can’t be any worse than lightning, and I’m not a bit afraid of that. Besides, if I am always going to live in this oil region, I ought to learn all about its dangers, so that I’ll know enough to keep away from them. Perhaps when I have grown to be a giant, like you, I will want to be a well-shooter too, and how can I if I haven’t learned how?”

This array of argument was too much for Brace to answer, and so, saying, “Well, I suppose I’ll have to take you with me just this once,” he chirruped to his horses, and, driving much more slowly and carefully than usual, turned into the road that led to the well he was engaged to shoot.

They reached the place without incident, and Arthur helped carry into the derrick the bundle of bright tin tubes that had been lashed to a couple of curved iron supports at one side of the wagon. He also helped place in position the reel on which was wound two thousand feet of stout cord, by means of which the torpedo was to be let down into the well. This line was run through a pulley that hung directly above the well, and its end terminating in an iron hook, dangled close to the mouth of the deep, dark hole.

When these preparations were made, Brace Barlow began to fit and fasten together several lengths of small tin pipe until they formed a continuous tube about fifty feet long. This is called the “anchor,” and was to be attached to the lower end of the shell, or large torpedo tube, so that when the whole was lowered into the well, it would support the torpedo at a height of fifty feet above the bottom.

Arthur was allowed to assist in fitting the anchor tubes, and also in making the shell ready to be filled with its deadly explosive. When the cans of nitro-glycerine were brought into the derrick, all the men employed about the place retired to a respectful distance from it. Then Brace insisted that Arthur should also go away, and leave him alone to finish the delicate and dangerous job of loading the shell, lowering it into position, and exploding it.

The boy begged to be allowed to stay, declaring that he was not in the least afraid, and would keep as still as a mouse. But Brace would not listen for a moment to his pleadings, and very slowly the little fellow walked away to what he considered a safe distance, though it was not nearly so far as the men had gone.

At this time the empty shell, which was a large tin tube about twenty feet long, was, with its anchor attached, hanging in the well so that its upper end was just above the surface. It hung from a very shallow iron hook, at the end of the stout cord arranged for the purpose; and Brace Barlow now proceeded slowly and cautiously to pour the nitro-glycerine into it. The stuff was the color of soft soap, and about as thick as syrup.

He had been thus engaged but a few minutes, when Arthur, who was nearer to him than anybody else, heard him call, “Come here, quick, somebody, and help me!”

Without a moment’s hesitation or thought of fear, the brave little fellow ran swiftly to the derrick, exclaiming, as he reached it, “Here I am, Brace! What do you want?”

“You here, you dear little chap!” cried the torpedo man, “I didn’t mean that you should come; but perhaps after all you will do better than another, and I must have help at once. You see the hook has slipped off the shell, and I only caught the torpedo in time to save it from dropping and exploding before I was ready. Then the weight of the cord pulled the hook up so that I can’t reach it. Now if you can climb up the side of the derrick, holding the drill rope in close to you till you reach the proper height, then swing out, catch hold of that hook, and slide down the drill rope with it in your hand, you will do what I want as well as if you were the biggest man in the world. Do you think you can?”

“I can try,” replied the boy, who took in the whole situation at a glance, and he at once began to climb the ladder that led to the top of the tall derrick.

It seemed that while Brace was filling the torpedo, and had nearly completed his task, he found it necessary to shift the position of the shell slightly. As he lifted it, the shallow hook slipped from the bail, or handle of stout copper wire, and flew up just beyond his reach. To let go of the torpedo was out of the question, for it would have fallen down the well and probably exploded from concussion with the iron tubing lining the hole before it had gone many feet. This explosion would have fired the quart or more of glycerine still remaining in one of the cans on the derrick floor, and Brace Barlow would instantly have disappeared from human view. The weight of the torpedo was so great that he could not support it very long; and so, unless assistance came to him promptly when he called, he must have let the thing drop, and suffered the consequences.

But help had come promptly; and a twelve-year-old boy, forgetting all thoughts of danger, and urged on by the love he bore his friend, was climbing the derrick, swinging out into space on the heavy drill rope, clutching the dangling iron hook, and sliding down with it in his hand. Then, instead of timidly reaching it to Brace, he stepped boldly up and attached it to the copper bail of the torpedo that was cutting deep into the flesh of the strong hand that held it, and must in another minute have let it go.

As the well-shooter, with a pale face, rose from his strained position, he clasped the boy in his arms, exclaiming: “Little one, you have done for me this day what any man might be proud of doing for a friend; and, so long as I live, I will never forget the service nor cease to be indebted to you.”

When the filling of the torpedo was completed, it was cautiously lowered a thousand feet to the bottom of the well, the “Go Devil,” a heavy, pointed bit of iron that was to explode it, was dropped, and, seizing Arthur in his arms, Brace Barlow ran swiftly from the spot.

A few seconds later the solid earth was shaken and there was a heavy but muffled roar. Directly afterwards a vast column of oil shot up through the derrick sixty feet into the air, and fell back to earth in a glistening cloud of amber-colored spray. The shot was a perfect success; and for months afterwards the old well again flowed at the rate of twenty barrels a day.

As Brace and his little friend rode homewards they stopped in the first lonely bit of forest to explode the still dangerous but empty nitro-glycerine cans. This was done by placing them on the ground, lighting the end of a short fuse attached to a cap thrust into one of them, and driving rapidly away. The explosion was terrific, and its roar was like that of a hundred-pounder gun. Arthur said it was better than any Fourth of July he had ever known.

CHAPTER V.

ARTHUR AND HIS COUSINS.

As Arthur and Brace Barlow returned from the well-shooting described in the preceding chapter, the latter set the boy down at a cross-road but a short distance from the Dustin house. Here the little fellow bade his “dear giant” good-night, and ran homeward, feeling happier than he had for a long time. Though he hardly realized the full value of the service he had just rendered to his friend, he was sure that he had been useful at a critical moment; he knew that he had been praised for what he had done, and he felt more manly than ever before.

It was quite late when he reached the front gate, where faithful little Cynthia was anxiously watching for him and wondering where he could be.

“Oh, Cynthia!” he cried, as he drew near and saw her, “I’ve had such a lovely time! I have been shooting a well with Brace Barlow, and I climbed up the derrick and got a hook that had slipped away from him, and brought it down; and he said I was a brave boy, and had saved his life, though I don’t see exactly how; and then we had a splendid Fourth of July time, blowing up the cans; and it sounded like a real truly cannon; and the very minute I get grown up I’m going to be a well-shooter.”

It was absolutely necessary for the enthusiastic little fellow to pour into sympathetic ear the tale of what he had done. He had performed a brave act, and in the first flush of his excitement he longed to be praised for it, as we all do whenever we have done anything that we consider especially good, or worthy of commendation. It is a reward of merit to which all who have earned it are entitled; and to withhold just praise is as cruel as to extend unjust censure.

Cynthia would not have been guilty of any such unkindness. Her eyes opened wide as she listened to the tale her Prince told of his own deeds, and she was just catching her breath to tell him how splendid she thought them, when they were startled by the sound of a harsh voice, calling, “Arthur! Cynthia! come into the house this minute, you naughty children. Don’t you know better than to be staying out there breathing the night air?”

“A boy must breathe some kind of air, Aunt Nancy, and when it is night time I don’t see how he can help breathing night air,” laughed Arthur, as he reached the house; for not even his aunt’s harsh tones could at once dispel his good spirits.

“What do you mean by talking back to me?” asked Mrs. Dustin. “I say that night air is poison, and no member of my family, even if he is a young interloper, shall breathe a drop of it, not so long as I can help it. Now, not another word. I know where you’ve been this whole blessed afternoon. You’ve been off with Brace Barlow, who ought to have more sense than to encourage your badness, shooting wells, and trying to get yourself blown into mince-meat, just to make more trouble for me. Yes, I know all about it, in spite of your sly ways. Now, you may go right to bed, and not a morsel of supper shall you have this night, which may be it’ll be a lesson that you will remember for one while, anyway.”

Mr. John Dustin, who sat smoking his evening pipe by an open window, rarely interfered with his wife’s management of the children; but now he spoke up saying:

“That won’t do, wife; you only gave the boy bread and water for his dinner, and it won’t do to send him to bed without any supper. I believe in proper punishment, where it is deserved, as much as anybody; but when it comes to starving, that’s quite another thing. It shall never be said that my brother Richard’s only son was starved in his uncle’s house. So give the boy his supper, and plenty of it. Then you can send him to bed if you see fit.”

Mrs. Dustin knew that when her husband spoke in this tone he meant to be obeyed; so, without a word, she set a plain but bountiful meal before Arthur. From a long experience of bread-and-water punishments and supperless nights the boy was wise enough to eat heartily all that he possibly could, in spite of his heavy heart. He ate in silence, and for some time nobody else spoke; only Dick, who sat at the farther end of the room with the other children, chuckled and made faces behind Arthur’s back, for the benefit, and to the huge delight, of his companions. He was greatly pleased at the result of his tale-bearing; for it was he who, overhearing Arthur tell Cynthia that he had been well-shooting with Brace Barlow, had hurried to the house, and repeated the information, with some picturesque additions of his own devising, to his mother.

Once, during the silent meal, little Cynthia tried to create a diversion in her cousin’s favor by remarking timidly to nobody in particular, but to the company in general, “Arthur says Brace Barlow says he saved his life.”

“Who says what?” inquired Mrs. Dustin, turning quickly and fixing her sharp eyes on the little girl’s face.

“Brace Barlow says—I mean Arthur says Brace Barlow says—he saved his——”

“Oh, fiddlesticks!” interrupted her mother; “you don’t know what you’re talking about. It isn’t at all likely that either of them did anything of the kind. The sort of danger Brace Barlow goes into is quick and sure. When it once gets started there isn’t any chance for life-saving, or for telling of it afterwards. Arthur ought to know better than to go round boasting in that way to a little girl like you, and I should think he’d be ashamed of himself for doing it.”

Arthur listened to this unjust speech with a flushed face and a feeling of choking indignation; but he did not say a word. Young as he was, he had already learned that in a contest with an unreasonable person silence is the weapon of wisdom.

After finishing his supper the forlorn little fellow, accepting his punishment without a murmur, though he could not imagine what wrong he had done, retired to his cot in the woodshed, where he was quickly blessed by the presence of sleep the comforter.

The next day was the bright one in September with which this story opens, and Arthur is introduced as he sits on the top rail of a zig-zag fence watching the other children at play.

Fired by the accounts of his adventure of the day before as narrated to them, at second-hand by Cynthia, for Arthur could not be induced to say another word concerning it, his cousins had determined to have a miniature well-shooting of their own. They spent the entire morning in the construction of a very shaky little derrick, about six feet high, and now they were busy drilling a well, which they hoped to put down to a depth of at least two feet. When it was finished they proposed to shoot it by means of a cannon-cracker, that they had saved over from the Fourth of July for use on some such special occasion.

The scheme was well planned, and seemed likely to be carried out; for the children were enthusiastic over it, and, under Dick’s direction, worked most diligently. Arthur would gladly have joined in this fascinating occupation; but the others would not have him. As Dick scornfully remarked: “What can a city chap like you know about building derricks and drilling wells? You wasn’t raised in the oil region.”

So Arthur was forced to content himself with sitting on the fence and watching them. Occasionally he turned for a chat with Uncle Phin, who was cutting brush in the field behind him, and who took a long rest whenever he reached the end of a row that brought him anywhere near his “lil marse.” Finally, after one of these rests, during which Arthur had paid no attention to the operations at the miniature derrick, he left his perch and followed Uncle Phin for a short distance into the thick brush.

CHAPTER VI.

A GALLANT RESCUE AND ITS REWARD.

Arthur had hardly left his perch before he was startled by a perfect babel of sounds coming from where the children were at play. There were yells and shouts of laughter, mingled with cries of pain and an angry screaming, together with piteous calls of “Arthur! oh, Arthur! Come and make ’em stop!”

Like a young deer the boy bounded out of the brush and over the fence, followed, much more slowly by Uncle Phin. Arrived upon the scene, he quickly comprehended the situation. In an unfortunate moment, just as the well was completed and ready to be shot, Cynthia’s dearly loved little white kitty came demurely walking in that direction looking for her mistress. At sight of the little animal a brilliant idea flashed through Dick’s mind, and he at once proceeded to carry it out. He said:

“We can’t have much fun shooting a dry well anyhow, ’cause there won’t be any oil to fly up in the air; but I’ll tell you what. Let’s have an execution by ’lectricity. It’ll be immense, and here’s the prisoner already waiting to be executed.”

Thus saying, the cruel boy snatched up the little white kitty, and, bidding the others hold Cynthia, who was ready to make a furious struggle in defence of her pet, he ran with it to the derrick. Here, with the make-believe drill rope, he hung it by the tail, so that the little pink nose was but a few inches from the ground. Then, lighting the fuse of the great cannon-cracker, he placed it directly beneath the victim, who was now uttering piteous cries of pain and terror, and ran to where the others were shouting with delight over the new and thrilling diversion so unexpectedly prepared for them.

Poor, desperate little Cynthia, kicking, biting, scratching, but struggling in vain with the young rascals who held her fast, began, as a last resort, to call upon Arthur, the brave Prince who had defended her against the big dog, and she did not call in vain.

Hatless and breathless, with the fire of righteous wrath blazing in his blue eyes, the plucky boy came flying to the rescue. He had no thought of the overwhelming odds against him. The princes of his fairy tales fought whole armies single-handed, and why should not he? His impetuous speed carried him right through the shouting group assembled to witness the execution of the hapless kitty, and two of them were flung to the ground before they knew of his presence. An instant later he reached the little derrick. The fuse had burned down into the body of the big cracker, and in another second it would explode. Without the faintest trace of hesitation, the little fellow seized it and flung it behind him.

An explosion followed almost instantly, and was accompanied by a yell of pain. The moment Dick recognized Arthur, and perceived his intention, he sprang after his cousin, and was directly in line when the cannon-cracker came flying toward him. It struck him and fell to the ground, exploding as it did so, and burning his bare feet painfully.

Furious with rage the cowardly young bully rushed at Arthur, who was releasing the white kitty from her unhappy position, and with a savage blow knocked the little fellow down. Then he jumped on him and began to pummel him, screaming “Take that, will you! And that! I’ll teach you! I’ll show you who’s boss round here!”

All at once these cruel cries were changed to yells of dismay, as, whack! whack! whack! a shower of stinging blows fell upon Dick’s shoulders. Uncle Phin, who had followed Arthur as fast as he was able, had arrived just in time to save his “lil Marse” from any severe injury at the hands of his enraged cousin, and to administer, with a stout stick, the thrashing that the young rascal so well deserved.

In less than a minute cowardly Cousin Dick and his frightened followers were scampering away towards the house, where they proposed to lay their side of the case promptly before their mother. Cynthia had gone after her beloved kitty, and brave little “Prince Dusty,” who had flung himself into Uncle Phin’s arms, was sobbing as though his heart would break.

“Soh, Honey, soh, don’t you cry now,” murmured the old man, in soothing tones. “’Member dat while you is a Dustin by name, you’s a Dale by breedin, an comes of Dale stock. You’s mos a man now, a young gen’lm’n, an it won’t nebber do fer sich as you is to cry like a lilly gal. Soh, now, Honey, soh.”

Neither of them heard the quick, determined step that approached them from behind, and so occupied was poor, troubled Uncle Phin in soothing and comforting his charge, that it was an easy matter for Mrs. Dustin to snatch the trembling boy from his arms. Then she marched rapidly away, without a word; but dragging her victim relentlessly after her.

Uncle Phin half started to his feet when he first realized what was happening; but sank back again with a groan, and a murmured “De good Lawd hab mussy on His Lamb.”

Then he bowed his frosted head on his knees and the hot tears trickled slowly between his black fingers.

While he thus sat helpless and despairing, poor Arthur was taken to the house and there whipped, until the apple-tree switch broke, and his Aunt Nancy’s strength was exhausted. Then, telling the boy that this was a lesson for him to remember as long as he lived, she bade him go to the woodshed, which was his sleeping-room, and stay there until she should release him.

During this undeserved punishment not a cry had escaped from the boy, nor had a tear found its way to his eyes. He bit his under-lip and clenched his hands, but not a sound did he utter. He remembered what Uncle Phin had just told him. He was almost a man now, and no man, especially a Dale, would cry for a whipping. So, though the little face was drawn and white, and the boy trembled until he could hardly stand, he held out to the end as bravely as ever a martyr under torture, and when he was thrust into his cheerless shed, he sat on the edge of his rude bed rigid and tearless. His mind was in a furious whirl, but above all was the overwhelming sense of injustice and outrage.

Finally he sprang to his feet, crying, “I hate you! I hate you! I hate you!” and then, flinging himself on his bed, he gave way to a burst of passionate weeping.

“Oh, mamma!” he cried, “my own mamma! why don’t you come for me and take me away from this dreadful place? I can’t stay here any longer! Indeed I can’t, mamma! oh, come for me; do come! Please, mamma, come for me, and take me to where you are!”

For nearly an hour the forlorn child cried for the dear ones who had left him; then his sobs gradually died away, and, utterly exhausted, he fell into a troubled sleep.

In the meantime little Cynthia, who only found her dear kitty after a long search, met her father coming home from his work, and when he inquired what was the matter with his daughter, and who had made her cry, she told him the truth of all that had happened, so far as she knew it. Mr. Dustin had begun to suspect that Arthur was ill-treated by his cousins, and as he listened to Cynthia’s story, his face grew very stern, and he said: “This matter must be looked into.”

When they reached the house, and he was told that Arthur had been severely punished for trying to kill Cynthia’s kitten, and for fighting with Dick who had rescued it, and that Uncle Phin had beaten Dick, Mr. Dustin’s anger could not be restrained. He said:

“Wife, I am afraid you have made a terrible mistake, and punished an innocent child for performing a noble act. If what Cynthia tells me is true, and I believe it is, Master Dick is the boy who tormented his little sister, and would have killed her pet. Master Dick is the coward who thrashed a little fellow two years younger than himself, for bravely rescuing the victim of his cruelty. Master Dick is the one who told a lie to hide his own wickedness and cause his cousin to receive the punishment he himself deserved. And Master Dick is the boy who is aching for the whipping that I shall give him before he is many minutes older.

“In regard to my dead brother’s child, I want it understood that so long as he remains under my roof he is never again to be punished for any fault, real or fancied; and if anybody has any complaints to make against him, they must make them to me. As for Uncle Phin, if it is true that he beat one of my children, he must leave this place, and look for a home elsewhere, which I shall tell him to-morrow.”

Every word of this was heard by the old negro, who was sitting on a bench in the little vine-colored porch, close under an open window, of the room in which Mr. Dustin stood. The old man, who had not known of the cruel punishment inflicted upon his “lil Marse,” was waiting patiently for Arthur to come out and bring him his supper, as the boy had done every evening since they came there to live.

Now he said to himself: “Dat’s all right, Marse Dustin. I did beat yo boy, an I do it agin if heem tetch my honey lamb; but yo sha’n’t nebber hab de chance to tun ole Phin Dale from yo house. No, sah; he done go of his own sef, befo ebber he ’lowin you to do sich a ting. An when he go he isn’t gwine erlone. No, sah.”

Just then little Cynthia came out with his supper, and said that Arthur was asleep. The old man ate his frugal meal in silence; but a train of thoughts was passing through his head much more rapidly than usual. They were all travelling in the same direction, and it was back toward his old Virginia home.

CHAPTER VII.

UNCLE PHIN’S PLAN.

After finishing his supper on the memorable evening of Arthur’s unjust punishment, Mr. John Dustin stepped softly into the woodshed, which, in that overcrowded household, had seemed to be the only place that could be given up for an extra sleeping-room. He closed the door behind him, and, by the light of a candle that he carried, gazed long and earnestly at the tear-stained face of the child who lay on a rude cot. It was hot and flushed, and the sleeping boy tossed and moaned as though visited by unhappy dreams. Once he called out: “Don’t let them whip me, mamma! I haven’t been naughty. Indeed I have not!”

At this the man, as though fearful of awakening the sleeper, hastily retired from the place, and there was a suspicious moisture in his eyes as he re-entered the other room.

Here he said: “Wife, I believe we have treated that little chap very unjustly. My brother Richard was the most truthful and honorable boy and man I ever knew, and I am inclined to think the son takes after his father. Hereafter I shall try to make his life pleasanter and happier, and in this I want you to help me.”

Mrs. Dustin made no answer to this, for her heart was hardened against the orphan lad, and she really believed him to be the sly bad boy that Dick strove to make him appear. “I will watch him more closely than ever, and show him up in his true light yet,” she thought, as she bent her head over her sewing so that her husband could not see her face. “He sha’n’t stand in the way of my children, and I’ll believe my own Dick’s word before his every time,” was her mental resolve.

Knowing nothing of his wife’s thoughts, Mr. Dustin was already taking steps to insure Arthur’s greater comfort. He went to the pantry and brought from it a bowl of milk, a loaf of new bread, and a plate of ginger cookies made that day. With these he again entered Arthur’s sleeping-room, and softly placed them on a chair where, by the light of the moon that was just rising, the boy would see them whenever he should awake. Once, while he was thus engaged, Mrs. Dustin opened her mouth to remonstrate against such a lavish provision of food for a mere child; but a glance at her husband’s determined face caused her to change her mind, and she wisely remained silent.

There had been another and more appreciative witness of Mr. Dustin’s thoughtful act. It was Uncle Phin, who, kneeling outside the shed and gazing through an open chink in its rough wall, was waiting patiently for the family to retire that he might have a private and undetected conversation with his “lil Marse.”

As Mr. Dustin again left the shed, the old man said softly to himself:

“De good Lawd bress you fer what you is jes done, Marse Dustin. You is got some ob pore Marse Richard’s goodness into you after all. If it warn’t fer de ole Miss an dem wicked chillun, me an lil Marse would try an stick it out awhile longer. But it can’t be did. No, sah, it can’t be did.” Here the old man shook his white head sorrowfully. “Dem young limbs is too powerful wicked, an ole Miss, she back ’em up. Fer a fac, ole Phin got ter tote his lamb away fum heah, an maybe de good Lawd lead us to de green fiels ob de still waters, where we kin lie down in peacefulness.”

An hour later, when the lights of the house were extinguished and all was still with the silence of sleep, Uncle Phin cautiously opened the shed door, and tip-toeing heavily to where Arthur lay, rested his horny hand gently on the boy’s white forehead.

The child opened his eyes and smiled, as, by the moonlight, now flooding the place, he saw who was bending over him.

“Sh-h-h, Honey,” whispered Uncle Phin, with warning finger uplifted; “git up quiet like a fiel mouse an come erlong wif me. Sh-h-h!”

Then the old man and the child stole softly away, the former not forgetting to carry with him the supply of food provided by Mr. Dustin. As quietly as two shadows they moved across the open space between the house and the barn.

Not until they were safe in his particular corner of the hay-mow did Uncle Phin venture to speak aloud. Here he drew a long breath of satisfaction, for in this place they could talk freely and without danger of being overheard.

First he made Arthur drink all that he could from the bowl of milk and eat heartily of the bread and cakes that Mr. Dustin had left for him. After eating the food, of which he stood so greatly in need, and which the old man assured him had been left by one “ob de good Lawd’s own rabens,” Arthur said:

“Oh, Uncle Phin, I’ve tried as hard as I can to be good, and make them all love me here, but they won’t do it. No matter what I do, it seems to be the wrong thing, and I only get punished for it. I am getting almost afraid to try and do right any more, and if we stay here much longer I’m pretty sure I shall grow to be a bad boy, such as my own dear mamma and papa wouldn’t love. Now don’t you think we might run away and live somewhere else, where it would be more easy to be good than it is here? Do you think it would be very wrong if we did? I’m sure Aunt Nancy would be glad to have us go, and perhaps Uncle John would too.”

“Why, Honeybug!” cried the old man delightedly, “dat ar is prezactly what yo ole Unc Phin’s been projeckin to hissef—only you mus’n’t call it runnin away, like you was a pore niggah. A Dale don’t nebber run away. He only change de spere ob his libbin, when he gits tired ob one place, an’ takes up wif anudder, same like we’s a gwine ter. I’s been considerin fer a long while back dat dese yere Dustins, who isn’t much better ’n pore white trash no how, wasn’t de bestest company fer a thorobred Dale like you is.”

“Hush, Uncle Phin! You must not speak so of my uncle’s family. He was my dear papa’s own brother, and they are the only relatives I have in the world,” said Arthur.

“No, dey isn’t, Honey. Dey isn’t de onliest ones what you got in de worl. You is got a granpaw libin yet. A monsrus fine gen’lm’n he is, and he’s place one ob de fines’ in all Ferginny, if I does say it. He’s quality, he is, an Dalecourt is yo own properest home.”

“But I have never seen my Grandpapa Dale, and he doesn’t know me, and I don’t believe he wants to,” replied Arthur; adding sadly: “There doesn’t seem to be anybody in the whole world that wants to know me, except you, and Brace Barlow, and Cynthia. Besides Dalecourt is a long way off, and it would take a great deal of money to get there, and we haven’t any at all, and I don’t believe even you could find the way to it if we should try and go there.”

“Dint I uster lib dere, Honey, and dint I come frum dere? What fo you spec I can’t go whar I come frum?”

“But coming from a place and going back to it are very different things,” replied Arthur, wisely.

“So dey is, Honey, ob cose dey is,” agreed Uncle Phin, who was not yet ready to disclose his plans.

“But we will go away somewhere and live together, won’t we?” pleaded Arthur. “I don’t suppose we could take my ‘dear Giant’ and Cynthia with us; but if we only could, wouldn’t we be happy?”

“Ob cose we’se a gwine leab dish yere place,” replied the old man. “You jes trus yo Unc Phin, an he fin a way to trabble, an a place fer to go.”

Then he told the boy that he should go away before daylight, and might remain several days making preparations for their journey. He would not say where he was going, because he wanted Arthur to be able to say honestly he did not know, if he were asked. He instructed the boy to collect all his little belongings, including his scanty wardrobe, and have them ready for a start at a moment’s notice. “Itll be in de night time, Honey, in de middle ob de night, an ole Phin ’ll creep in an wake you, same like he did erwhile ago. So don’t you be afeared when you wakes up sudden an fin’s him stan’in alongside ob you.”

“No, I won’t be afraid, and Ill be ready whenever you come for me,” replied the little fellow; “but don’t stay long away, because I shall be so lonely without you.”

Uncle Phin promised that he would not be a single minute longer than was necessary to make preparations, and Arthur was about to go back to the house, when a sudden thought flashed into his mind, and he exclaimed: “Oh, my book, my precious book that the beautiful lady gave me! I can’t leave it behind, and Im afraid Aunt Nancy won’t let me have it.”

Then, in answer to Uncle Phin’s inquiries, he had to tell him the whole story of his adventures as a Prince, which he had not heretofore found an opportunity of relating, and in which the old man was greatly interested. He was particularly pleased with the title bestowed upon his “lil Marse” by the beautiful lady, and said: “You is a shuah ’nough Prince, Honey, if dere ebber was one in dis worl, only you won’t always be Prince Dusty. Some day youll be a Prince somefin else. But you mus hab yo book, in cose you mus, an we’ll make out to git hol ob it somehow or nudder.”

Comforted by this assurance, and filled with the new hopes raised by their prolonged conversation, Arthur flung his arms about the old man’s neck and kissed him good-night and good-bye. Then slipping from the hay-mow he sped back to the house, carrying the empty dishes, from which Uncle Phin had taken the remnants of food for his own use.

CHAPTER VIII.

AWAKENED AT MIDNIGHT.

The next morning Mrs. Dustin was greatly surprised on coming down-stairs to find that no fire had been made in the kitchen stove, and that the water-buckets, standing on a shelf over the sink, were empty. Nothing of this kind had happened since Arthur and Uncle Phin came there to live, nearly two months before; for to light the fire and bring fresh water into the house were among the very first of Uncle Phin’s morning duties. Arthur had meant to get up very early this morning and do these things, with a vague hope that the old negro’s absence might not be noticed; but he was so thoroughly exhausted by the events of the preceding day and night, that he overslept and only awoke with a start as his Aunt Nancy entered the kitchen.

Now, wide-awake, the boy lay trembling in bed and wondered what would happen. He heard his aunt go out to the barn and call “Phin! Uncle Phin!” but there was no answer, though the call was repeated several times. Then she came back muttering something about “lazy and worthless old niggers,” and Arthur heard her making the fire. Still anxious to take Uncle Phin’s place as far as possible, he jumped up, and hastily slipping on his ragged clothes, picked up an armful of wood that he carried into the kitchen.

His aunt looked at him sharply: “Where is Phin?” she demanded.

“I do not know,” answered the boy.

“Humph! I might have expected you would say that,” she replied. “How did you know I wanted any wood, then?”

“I heard you calling Uncle Phin, and thought perhaps that was what you wanted him for,” was the reply.

“Well, then, if you know so well what I want, perhaps you know that I want you to get out of this kitchen and keep out of the way while I am getting breakfast,” said Mrs. Dustin, angrily.

It is always those whom we have injured the most that we dislike the most; and, with the recollection of her cruelty toward this gentle child fresh in her mind, the mere sight of him filled her with anger.

So the little fellow wandered out to the barn, and felt very lonely as he climbed up on the hay-mow to make sure that his dearest earthly friend had indeed gone. He sat down to wonder where Uncle Phin was, and how long it would be before he would come to take him away from that unhappy place. He wished that he might stay right where he was, and not be compelled to see any of the family again, and was feeling very wretched and forlorn generally. All at once he heard Cynthia’s voice calling the chickens around her on the barn floor where she fed them every morning. Here was somebody for whom he cared, and the thought that he was so soon to leave her, probably forever, filled him with a pang of mingled pain and love.

He slid down from the hay-mow to where his little cousin stood, and as she threw her arms about his neck and kissed him and told him how much she loved him and how sorry she was for him, he began to realize how hard it would be to part from her, and to wonder if after all he ought to run away with Uncle Phin.

Cynthia was a loving and lovable little soul, and though she had a freckled face, it was lighted by a pair of glorious brown eyes. Her hair was of a rich brown, flecked with specks of red gold where the sunlight shone through it. It was just such hair as the sun loves to kiss, and the merry wind delighted to toss it into the most bewitching tangles whenever it was not closely imprisoned under the little pink sun-bonnet. It reminded Arthur of his own dear mother’s hair, and often when they were playing together he would snatch off the pink sun-bonnet just for the pleasure of seeing it ripple down over her shoulders. His own used to be long, almost as long as Cynthia’s, but his Aunt Nancy had cut it off when he first came to live there, and it had been clipped short ever since, greatly to Uncle Phin’s sorrow.

While Arthur and Cynthia were feeding the chickens, and the former was almost forgetting his recent loneliness, Mr. Dustin came into the barn. He greeted both the children pleasantly, and even kissed them, a thing that Arthur wondered at, for he could not remember that it had ever happened before. Then he asked, “Do you know where Uncle Phin is, Arthur?”

“I think he has gone away,” replied the boy, flushing and looking down, for it seemed somehow as though he were not exactly telling the truth.

“Do you know where he has gone?”

“No, sir, I do not,” was the honest reply, and the boy looked his questioner squarely in the face as he made it.

“Well, I believe you, of course,” said his uncle, “and I suppose he must have taken it into his head to leave us, though it seems very strange that he should have done so without bidding you good-bye, or telling you where he was going.”

This was too much for Arthur’s sense of honor, and speaking up manfully, he said: “He did tell me he was going away, Uncle John, and bid me good-bye but he didn’t tell me where he was going, and he didn’t want me to say anything about it unless I had to.”

“I am glad you have told me this,” said Mr. Dustin, “and since he has gone I must say I am not very sorry. Now come in to breakfast.”

That morning Mr. Dustin took Arthur and Cynthia with him to the well he was drilling, and, to their great delight, allowed them to stay there all day. When they reached home that evening Arthur was so emboldened by his uncle’s unusual kindness, that he ventured, in his presence, to make mention of the book of fairy tales that his Aunt Nancy had taken from him. He said:

“Isn’t the book the beautiful lady gave me my very own, Aunt Nancy?”

“I suppose it is,” answered Mrs. Dustin, shortly.

“Well, then, don’t you think I might have it just to look at?”

“I said you might have it when I got ready to give it to you.”

Then Mr. Dustin inquired what book they referred to, and when it was explained to him he said:

“Well, I guess your aunt is ready to let you have it this very minute, aren’t you, wife?”

There was no mistaking his meaning; and, very ungraciously, Aunt Nancy took the precious book down from its high shelf and tossed it on the table.

Arthur seized it eagerly, and until the children were sent to bed they and Mr. Dustin enjoyed looking at its many beautiful illustrations. That night Arthur slept with it under his pillow and it must have influenced his dreams for they were very pleasant ones.

The following day was also a happy one for Arthur and Cynthia, for they spent most of it sitting close together under the roots of the great overturned tree that was their especial retreat absorbed in the book, and discussing, in their wise childish way, several of its charming stories that Arthur read aloud to his little cousin.

The boy was beginning to think that life in this place was not so very cheerless after all, and was becoming more than ever doubtful of the expediency of running away, when an incident took place that restored all his previous resolves. Cynthia had been called in by her mother to sew on her hated patchwork, and Arthur was sitting alone, when suddenly a great, squirming, half-dead snake was dropped on him from above. With a cry of horror the startled boy sprang up just in time to see his Cousin Dick’s grinning face, and hear him say, “That’s only part of what you’ll get before long, you little sneak, you.”

That night as he slept with his precious book clasped tightly in his arms, he was again awakened by a hand laid lightly on his forehead. As he sprang to a sitting posture, Uncle Phin bent lovingly over him, saying:

“Sh-h-h, Honey! Ebberyting’s ready, an it’s high time fer us to be gittin away frum hyar.”

CHAPTER IX.

A HURRIED FLIGHT.

There was no need for Arthur to ask any questions, when he was roused in the middle of the second night after Uncle Phin’s departure. He realized at once what was required of him, and the heaviness of sleep instantly vanished, leaving him keenly wide awake. Stepping softly from his bed, he quickly dressed, while the old negro gathered together everything belonging to his “lil Marse,” and placed the things in a corn-sack that he had brought for that purpose.

“Is dat yo book, Honey?” he whispered, noticing the volume of fairy tales lying on the bed.

“Yes, that is my own precious book that the beautiful lady gave me; but don’t put it in the bag, Uncle Phin, I want to carry it myself.”

Then the thoughtful little fellow, since he could not bid Cynthia good-bye, and feared she might feel hurt if he went away without a word, begged his companion to wait, just a minute, while he wrote her a note. He wrote it by the bright moonlight, on a bit of brown paper, with the stump of a lead-pencil, so that it was not a very elegant production, but it answered its purpose, and was tenderly cherished for many a day by the little girl who received it the next morning. In it, in a big, scrawling hand, was written:

“Dear Cynthia: I have been so much trouble here, specially to Aunt Nancy and Dick, that I am going away with uncle Fin, to find another home. I love you dearly, and sometime I hope I shall come back and see you. Good-bye, from

Although the old negro was in a hurry to be off, he waited patiently while Arthur slowly wrote this note. To him writing was one of the most mysterious and difficult of arts; and, gazing admiringly at the young penman, he murmured to himself:

“What a fine lilly gen’l’man him be to be shuah. Him only twelve year ole; but settin dar an er writin like he was a hundred.”

When the note was finished it was pinned to the pillow of the cot bed, and, with a lingering look at the place that had sheltered him for a year, the child stepped out and softly closed the door. Then clasping his precious book tightly under his arm, and trustingly following the old negro, Arthur started on the wonderful journey that was to change the whole course of his life, though he was still ignorant of their destination.

When they were safely behind the barn, out of sight and hearing of the house; Uncle Phin stopped and said:

“Dere’s only one ting trubblin dis yeah ole woolly head. Kin you tell, Honey, fer shuah, what way de ribber ober yander is a runnin’?”

“Which, the Alleghany? Why, south, of course,” answered Arthur, wondering at the question.

“Dat’s what I lowed it done!” exclaimed the old man. “I knowed it didn’ run yeast, kase dat ar way de sun rise, and I knowed it didn’ run wes, kase dat ar way him a settin; but I wasn’ rightly shuah him didn’ run to de norf. I was figgerin all de time dough on him running to de souf, an now we’m git back to ole Ferginny easy an sartin.”

“To Virginia!” cried Arthur, in dismay. “Are we going to try and go way to Virginia, Uncle Phin?”

“Ob cose we is, Honey. We’se er gwine to Ferginny, an Dalecourt, an yo granpaw, an de lil ole cabin by the magnole tree. We is gwine to yo own shuah ’nough home, Honey.”

“But how are we ever going to travel so far?”

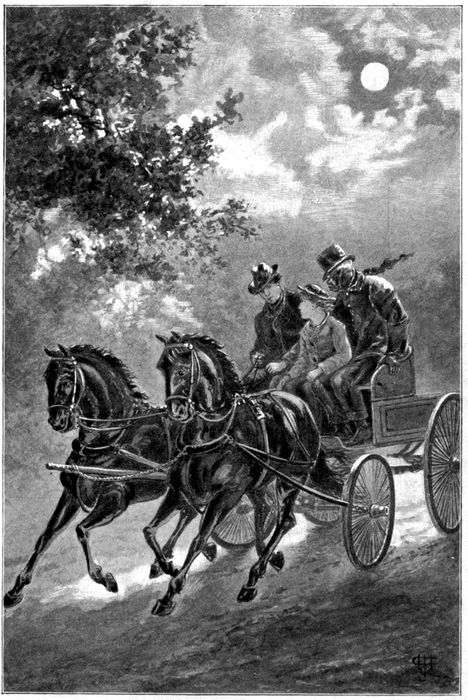

“You’ll see, Honey! you’ll see dreckly,” chuckled the other. “I’se got a great ’sprise in sto fer you. Hyar’s de kerridge a waitin on us now, and Misto Barlow is gwine dribe us to the steamboat.”

They were now on the road, at some distance from the house, and as Uncle Phin spoke, Arthur saw, drawn up to one side in the shadow of a clump of trees, Brace Barlow’s team, and, leaning against the light wagon, the young man himself.

“Oh, Brace!” he cried, springing forward the moment he saw who it was, “I’m so glad! I didn’t want to go away without seeing you again. Are you really going with us?”

“I wish I could go with you all the way, my boy, and see you safe to your journey’s end, but you know I can’t leave my old mother. So I am only going to give you a lift for a little way and see that you get a good start. Jump in quick now for we’ve got a long drive ahead of us and I must be back by daylight.”

As the spirited horses dashed away over the moonlit road with Arthur nestled between Brace and Uncle Phin on the single seat of the wagon, the boy learned how it happened that his friend had been induced to aid them in their flight. Uncle Phin had gone directly to him two nights before, and roused his indignation by describing the unhappy life his young charge was leading, and how much he suffered at the hands of Mrs. Dustin and her children. Then he told Brace of Dalecourt, and gave him to understand that Colonel Dale was ready to receive his grandson with open arms, whenever he should go to him.

The kind-hearted young fellow, entertaining a sincere regard for the little chap who had recently rendered him so great a service, readily agreed to a plan that promised so much of good to the boy, and willingly consented to assist him and Uncle Phin to make a start on their journey. He devoted two whole days to the task of preparing for it, and did so much more than Uncle Phin had dared ask or hope for, as to win the old man’s everlasting gratitude and render the first stage of their journey comparatively easy.

A HURRIED FLIGHT BY MOONLIGHT.

For some time Arthur enjoyed the exciting night ride over the steep mountain roads, across deep valleys, and through forests, all bathed in the glorious, unclouded moonlight. He did not ask whither he was being taken. Nestled warmly between his two best friends he felt perfectly safe and happy. He knew that they would do what was best for him, and the very mystery and uncertainty attending this part of their journey lent it a fascination. At length his weary head nodded, the heavy eyelids closed, and, sound asleep, he was unconscious of his surroundings until the horses stopped, and he awoke to find himself being lifted from the wagon.

There was a gleam of moonlit water in his eyes, and as he dimly realized that he was on the bank of a river, strong arms bore him into the cabin of a queer-looking craft that lay moored to the forest trees. Here the boy was gently laid down, and was vaguely conscious that Brace Barlow was bidding him good-bye, when the sleepy eyelids again closed and the child passed into dream-land.

The young man stood looking at the sleeping boy for a full minute. As he did so he said softly: “Dear little chap! I hate to have you go away, and to think I may never see you again. But I suppose it’s the best thing to be done, or I wouldn’t have lifted a hand to help it along. I only hope it will come out all right, and that you’ll have a happier life in the place you’re going to than you ever could have had here. God bless you.”

It was a benediction, as well as the farewell of one brave soul to another. As he uttered it the young man slipped a bank bill between two pages of the book the boy had clasped so closely, but which had now fallen from his hands.

“It’s little enough,” he said to himself as he turned away, “but it’s all I’ve got, and may be it will help him out of a fix some time.” Then he went out to assist Uncle Phin, who was casting off the fastenings of the boat, and preparing to push it from the shore.

In another minute the clumsy old craft had swung clear of the bank, and was moving slowly down stream in the shadow of the great trees that grew to the water’s edge. Brace Barlow watched it until it became a part of the shadows, and he could no longer distinguish the white-headed figure bending over the long sweep that was made to do duty as a steering oar or rudder. Then he again mounted the seat of his light wagon, and started on his long homeward drive, feeling more lonely than he had ever felt in all his life.

CHAPTER X.

ON BOARD THE ARK.

The craft on which the old man and the sleeping boy were now slowly drifting down the broad, moonlit stream, was a tiny house-boat, such as are common on all American rivers. It had floated down, empty and ownerless, with the high waters of the preceding spring, and had stranded and been left by the receding flood at the point where Uncle Phin discovered it some weeks before. It was a small, flat-bottomed scow, on which was built a low house, ten feet long and six wide. This house contained but a single room; and beyond it, at either end, the deck of the scow projected about four feet. At each end of the house was a door, and on each side a square hole or window, that closed with a wooden shutter.

At the stern was a steering oar, as has been stated. It hung on a swivel and its long handle projected up over the end of the roof, on which the steersman stood. From each side of the roof hung a heavy sweep, by means of which the craft might be slowly propelled or turned in any desired direction. When not in use, the lower ends of these could be lifted from the water by ropes attached to their blades, and fastened to the sides of the house. A rude ladder reached from each of the small end decks to the top of the roof. The whole affair was strong and in good condition, but rough and unpainted.